Follow-up experiments in mice pointed to a prospective explanation for why: the deletion appeared to limit male animals size when fed a calorie-restricted diet plan. “In other words, the deletion seems to be protective versus that particular metabolic syndrome,” states Gokcumen.To even more question the link between malnutritions impacts and GHRd3, the group utilized CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out the third exon from the mouse variation of the gene, generating a murine model of the gene variant. That revealed a sex-specific distinction: when male mice bring the deletion were fed a calorie-restricted diet plan, they ended up weighing the very same as their female equivalents, while in wildtype mice, male mice were constantly larger than women (the deletion had no result on female mouse weight). The cyclical daily expression pattern of GHR typically seen in male mice was dampened in those with the removal.” It appears that the calorie-restricted male mice with the deletion end up revealing a female-like transcriptome in their liver, which in turn, we believe, leads to a lack of sexual dimorphism in size,” Gokcumen composes in an e-mail to The Scientist.Linking these results back to the evolutionary history of GHRd3, Gokcumen states males might benefit from being smaller in resource-limited environments, but when resources are plentiful, being bigger may assist protect mates.

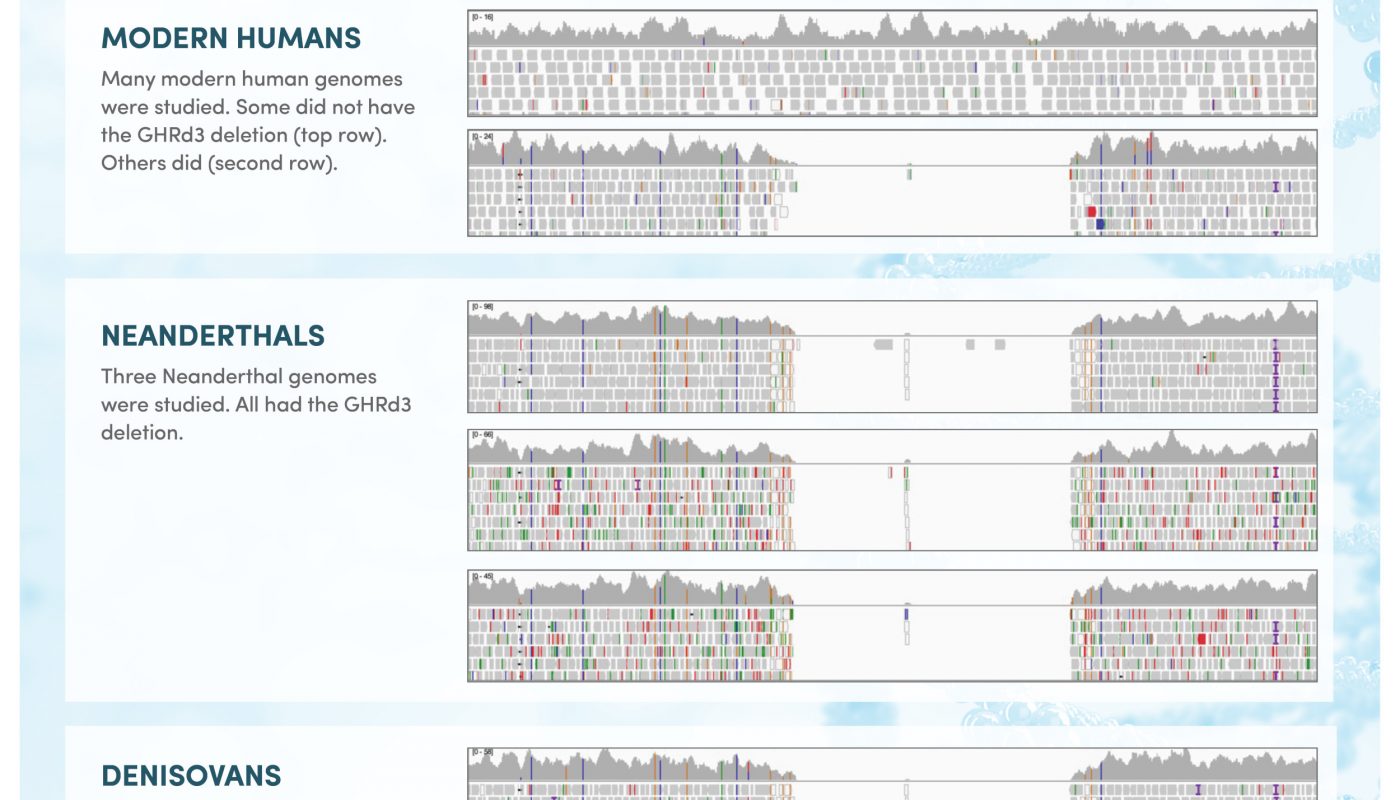

A globally uncommon version of the growth hormone receptor likewise seen in Denisovans and Neanderthals may have assisted our forefathers survive periods without food, a brand-new research study published on September 24 in Science Advances claims.Reconstructing the evolutionary history of a particular variant of the growth hormonal agent receptor gene (GHR) variation– the so-called GHRd3 variation, which is defined by a deletion of the genes 3rd exon– scientists have actually found that its frequency declined sharply around 40,000 years earlier. Follow-up experiments in mice pointed to a potential explanation for why: the removal appeared to limit male animals size when fed a calorie-restricted diet plan. This sort of development limitation could assist males survive lean times but limit their reproductive success in times of plenty.” This paper is amazing due to the fact that it highlights the power of combining evolutionary analyses of ancient and contemporary genomes with in-depth molecular characterization of the impacts of genetic versions,” writes Tony Capra, a specialist in evolutionary and computational genomics at the University of California, San Francisco, in an email to The Scientist. ” I think that the context-dependent complexity revealed here for the impacts of the GHRd3 version (in terms of sex and environment) are most likely common. We just havent had the ability to check out the molecular results of other variants with evidence of recent selection in such detail.” In previous work, Omer Gokcumen, an evolutionary biologist at the University at Buffalo, and his colleagues scanned Neanderthal, Denisovan, and ancient and modern-day Homo sapiens genomes for shared structural gene variants (such as deletions), with the goal of discovering ones that have “been lurking around since we were Homo erectus,” states Gokcumen. One such variation that they recognized was GHRd3, so for the new research study, they dug deeper into its evolutionary history and potential function, to get at why it may have continued for so long.Initially, the scientists assumed that the variation might have been preserved by a phenomenon called the heterozygous advantage, where individuals that bring both variations of a gene (are heterozygous) have an advantage over individuals who carry duplicates of one version (are homozygous). A well-known example for this is the sickle cell allele, which protects heterozygous carriers from some kinds of malaria. However this did not fit with GHRd3s reconstructed evolutionary history. Instead of being preserved at steady levels throughout human history, GHRd3 emerged as the dominant development hormone receptor allele in ancient human beings approximately 1 million to 2 million years ago, and it remained that method for an extremely long time, up until 30,000 to 40,000 years earlier, when it quickly declined in frequency in much of the world, an indication of modification in choice pressure. “This was really interesting because you rarely see selection on human variation,” Gokcumen explains. That asked the concern: Why did the deletion all of a sudden become mainly adverse in the Upper Paleolithic, after seeming beneficial previous to that? In the literature, GHRd3 is associated with smaller birth size, early onset of puberty, and increased durability– qualities that Gokcumen observed are also related to a starvation-related phenomenon referred to as “catch-up growth,” where growth later on in life makes up for smaller birth weight and size due to malnutrition. The team decided to look closer at GHRd3s prospective function in starvation resilience by taking a look at the frequency of the deletion amongst kids in Malawi who had endured poor nutrition. The deletion was less typical in children who exhibited a more serious response to poor nutrition called Kwashiorkor, that includes edema, loss of muscle mass, and a prolonged tummy, than in children with a less-severe action. “In other words, the removal appears to be protective against that particular metabolic syndrome,” states Gokcumen.To even more interrogate the link in between malnutritions results and GHRd3, the team used CRISPR-Cas9 to knock out the third exon from the mouse variation of the gene, generating a murine model of the gene variation. That exposed a sex-specific distinction: when male mice bring the deletion were fed a calorie-restricted diet, they wound up weighing the like their female counterparts, while in wildtype mice, male mice were constantly larger than women (the deletion had no result on female mouse weight). “This removal might be helpful, for males especially, to survive under resource-restricted conditions,” Gokcumen says.A sex-specific impact of the deletion might not be so surprising, as there are sex-dependent distinctions in GHR gene expression in the liver, a location where the growth hormone receptor is highly revealed. While male mice generally show a cyclical day-to-day expression pattern of GHR, the expression is steady in female mice. In the study, female mice showed this stable GHR expression throughout the day no matter which allele they carried. The cyclical day-to-day expression pattern of GHR usually seen in male mice was dampened in those with the deletion. And downstream of the modified GHR expression, the researchers discovered a number of genes that were differentially revealed in males with and without the exon deletion.” It seems that the calorie-restricted male mice with the removal wind up expressing a female-like transcriptome in their liver, which in turn, we think, leads to a lack of sexual dimorphism in size,” Gokcumen writes in an email to The Scientist.Linking these results back to the evolutionary history of GHRd3, Gokcumen says males might take advantage of being smaller in resource-limited environments, but when resources are abundant, being larger might help secure mates. In that method, the removal “might be detrimental for physical fitness if hunger is not a huge deal,” Gokcumen writes. Gokcumen and his group assume that ancient people and Neanderthals may have dealt with starvation more frequently, and that with the innovation of tools that would have increased the flexibility of their diet plan, resource constraints ended up being less important in between 70,000 and 30,000 years ago, accompanying the decline of GHRd3.While that idea creates a coherent story, it leaves some aspects of GHRd3 unusual, states University of Haifa and Albert Einstein College of Medicine geneticist Gil Atzmon, who has actually looked into GHRd3. Particularly, the current geographic distinctions in frequency: nearly 50% of the population carries the allele in some African populations, while it is much rarer in populations in East Asia. “Invention of tools … should have [impacted] the world equally basically and not as we see [in the paper] more in China and less in Africa,” writes Atzmon in an email. Capra agrees, composing that “the characteristics and possible chauffeurs of the decrease in frequency with time and geography require more investigation.”