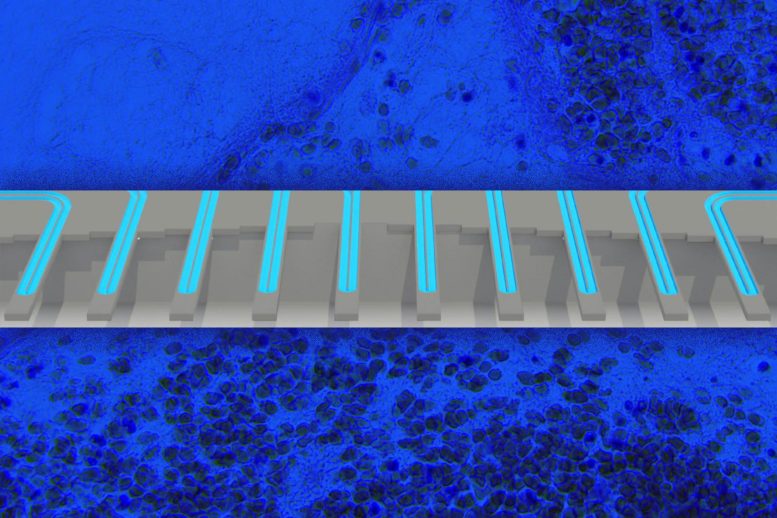

Researchers at MIT and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have actually established a new method to determine whether a specific cancer client will respond to a particular drug. Their technique involves exposing cells to the drug and then determining modifications in their mass using a device similar to the one shown.

A new research study reveals a link between client survival and modifications in tumor cell mass after glioblastoma treatment.

Scientists at MIT and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have established a new way to identify whether specific clients will respond to a specific cancer drug or not. This type of test might help medical professionals to choose alternative therapies for patients who do not respond to the therapies usually used to treat their cancer.

The new technique, which includes getting rid of tumor cells from clients, treating the cells with a drug, and after that determining changes in the cells mass, could be applied to a wide range of cancers and drug treatments, says Scott Manalis, the David H. Koch Professor of Engineering in the departments of Biological Engineering and Mechanical Engineering, and a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research.

Researchers at MIT and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have developed a new way to figure out whether a private cancer client will respond to a specific drug. Patients who have this marker normally react better to the drug. For clients who dont react to TMZ, there are a handful of alternative drugs readily available, Ligon says, or clients can select to get involved in a clinical trial.

In their brand-new study, the scientists chose to see if an easier and considerably much faster technique– measuring subtle changes in single-cell mass circulations between drug-treated and neglected cancer cells– would be able to predict client survival. They carried out a retrospective research study with a set of live glioblastoma tumor cells from 69 clients, donated to the Ligon lab and the Dana-Farber Center for Patient Derived Models, and utilized them to grow spheroid tissue cultures.

” Essentially all of the scientifically utilized cancer drugs either directly or indirectly stop the growth of cancer cells,” Manalis says. “Thats why we think measuring mass might use a universal readout of the results of a lot of various types of drug systems.”

The brand-new research study, which focused on glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer, becomes part of a collaboration between the Koch Institute and Dana-Farber Precision Medicine programs to discover brand-new biomarkers and diagnostic tests for cancer.

Manalis and Keith Ligon, director of the Center for Patient Derived Models at Dana-Farber and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School, are the senior authors of the study, which was released on October 5, 2021, in Cell Reports. The lead authors of the paper are Max Stockslager SM 17, PhD 20 and Dana-Farber research professional Seth Malinowski.

Determining cancer cells

Glioblastoma, which is diagnosed in about 13,000 Americans each year, is incurable, however radiation and drug treatment can assist to extend patients expected lifespan. Many do not survive longer than one to two years.

” With this illness, you dont have much time to make changes. So, if you take an inadequate drug for six months, thats pretty considerable,” Ligon says. “This sort of assay might help to accelerate the knowing process for each individual client and help with decision-making.”

Clients identified with glioblastoma are usually provided a chemotherapy drug called temozolomide (TMZ). This drug just assists about 50 percent of patients.

Currently, physicians can utilize a hereditary marker– methylation of a gene called MGMT– to predict whether clients will react to TMZ treatment. Patients who have this marker usually respond much better to the drug. The marker does not provide trusted forecasts for all patients due to the fact that of other genetic aspects. For clients who dont react to TMZ, there are a handful of alternative drugs offered, Ligon says, or patients can choose to take part in a clinical trial.

In the last few years, Manalis and Ligon have been dealing with a new method to forecasting client reactions, which is based upon measuring how tumor cells respond to treatment, instead of genomic signatures. This technique is called functional accuracy medicine.

” The idea behind functional precision medication is that, for cancer, you might take a patients tumor cells, provide the drugs that the client may get, and forecast what would take place, prior to providing them to the client,” Ligon states.

Scientists are working on many different techniques to practical accuracy medication, and one technique that Manalis and Ligon have actually been pursuing is determining modifications in cell mass that occur following drug treatment. The technique is based upon a technology developed by Manalis laboratory for weighing single cells with incredibly high precision by streaming them through vibrating microchannels.

Numerous years ago, Manalis, Ligon, and their colleagues demonstrated that they could use this innovation to examine how 2 types of cancer, glioblastoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia, react to treatment. This result was based on determining private cells several times after drug treatment, allowing the researchers to compute how their development rate changed in time following treatment. They revealed that this figure, which they called mass build-up rate (MAR), was strongly predictive of whether the cells were vulnerable to an offered drug.

Using a high-throughput variation of this system, which they established in 2016, they might calculate an accurate MAR using just 100 cells per client. Nevertheless, a disadvantage to the MAR technique is that the cells should remain in the system for a number of hours, so they can be weighed again and again, in order to compute the development rate in time.

In their brand-new research study, the scientists decided to see if a simpler and considerably much faster method– measuring subtle changes in single-cell mass distributions between drug-treated and untreated cancer cells– would have the ability to anticipate patient survival. They carried out a retrospective research study with a set of live glioblastoma growth cells from 69 clients, donated to the Ligon lab and the Dana-Farber Center for Patient Derived Models, and utilized them to grow spheroid tissue cultures. After separating the cells, the researchers treated them with TMZ and then determined their mass a couple of days later on.

They found that by just determining the mass distinction between cells prior to and after treatment, utilizing as few as 2,000 cells per client sample, they could accurately predict whether the client had reacted to TMZ or not.

Much better predictions

The scientists showed that their mass measurement was just as accurate as the MGMT methylation marker, however mass measurement has actually an added benefit because it can work in clients for whom the genetic marker doesnt reveal TMZ vulnerability. For numerous other types of cancer, there are no biomarkers that can be utilized to forecast drug response.

” Most cancers do not have a genomic marker that can be used at all. What we argue is that this practical technique might work in other circumstances where you do not have any choice of a genomic marker,” Manalis says.

Since the test works by measuring changes in mass, it can be used to observe the results of several kinds of cancer drugs, no matter their system of action. TMZ works by arresting the cell cycle, which causes cells to become bigger since they can no longer divide but they still increase their mass. Other cancer drugs work by disrupting cell metabolic process or harming their structure, which also impact cell mass.

The scientists long-lasting hope is that this method could be utilized to evaluate several various drugs on an individual clients cells, to predict which treatment would work best for that client.

” Ideally we would evaluate the drug the client was more than likely to get, however we would also test for things that would be the backup strategy: first-, second-, and third-line therapies, or different mixes of drugs,” says Ligon, who also functions as chief of neuropathology at the Brigham and Womens Hospital and a specialist in pathology at Boston Childrens Hospital.

Manalis and Ligon have co-founded a business called Travera, which has actually certified this innovation and is now gathering data from client samples from several different types of cancer, in hopes of establishing medically verified lab tests that can be utilized to assist patients.

Recommendation: “Functional drug vulnerability screening using single-cell mass forecasts treatment outcome in patient-derived cancer neurosphere designs” by Max A. Stockslager, Seth Malinowski, Mehdi Touat, Jennifer C. Yoon, Jack Geduldig, Mahnoor Mirza, Annette S. Kim, Patrick Y. Wen, Kin-Hoe Chow, Keith L. Ligon and Scott R. Manalis, 5 October 2021, Cell Reports.DOI: 10.1016/ j.celrep.2021.109788.

The research study was moneyed by the MIT Center for Precision Cancer Medicine, the DFCI Center for Patient Derived Models, the Cancer Systems Biology Consortium of the National Cancer Institute, and the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant from the National Cancer Institute.