A new study has actually shed new light on why big mammals passed away out at the end of the glacial epoch, recommending their extinction was triggered by a warming environment and expansion of vegetation that developed inappropriate environment for the animals. The findings, released in the journal PNAS, have major ramifications for proposals to avoid the soils in the Arctic today from thawing by re-introducing animals such as bison and horses.

About 14,000 years ago, at the end of the last glacial epoch, open, grassy landscapes that had extended eastwards from France across the now immersed Bering Sea all the method to the Yukon in Canada were transformed by the quick spread of shrubs. At the exact same time, numerous renowned mammal types that occupied what is now Alaska and the Yukon, such as the woolly massive, became extinct, and archaeology records human presence in the region.

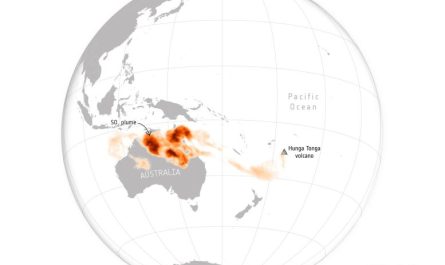

Today, with strong arctic warming, shrubs are spreading out even further north into tundra areas. It is now popular to promote that a kind of rewilding– where animals are returned to their initial communities to bring back more “natural” conditions– might reverse the trend of increasing shrub cover, with possible advantage of keeping carbon saved in the ground. By focussing on records that satisfied rigorous dating criteria the team could precisely determine the timing of shrub expansion throughout this area. Benjamin Gaglioti of the University of Alaska-Fairbanks added “The hypothesis that reestablishing megafauna will avoid or slow warming-driven permafrost thaw and plant life modification in the Arctic has been reinforced by the concept that Pleistocene megafauna were instrumental in preserving ice age environments.

These ancient coincidences have led to the suggestion that human searching caused the death of the mammals, and their loss led to the shrub expansion, as they were not there to trample down the vegetation and put nutrients back into the soil.

Today, with strong arctic warming, shrubs are spreading even further north into tundra areas. It is now popular to advocate that a form of rewilding– where animals are gone back to their initial environments to bring back more “natural” conditions– might reverse the pattern of increasing shrub cover, with possible advantage of keeping carbon kept in the ground. This is since low-growing plant life exposes the ground to cooler conditions than shrub cover does, and therefore the ground and the carbon it includes stay well frozen.

Others advocate that environment modification drove the greenery and landscape changes, and these led to the loss of the animals as their habitat disappeared.

To check these alternative hypotheses, a worldwide research group taken a look at records of fossil pollen preserved in lake sediments throughout Alaska and Yukon for thousands of years. By concentrating on records that satisfied rigorous dating requirements the team could precisely identify the timing of shrub expansion across this area. They then compared this with how the varieties of radiocarbon-dated bones from horse, bison, massive and moose altered through time– which provided them with a quote of their changing population sizes.

Their results revealed that willow and birch shrubs began to expand across Alaska and Yukon around 14,000 years earlier, when records of dated bones suggest that big grazing mammals were still abundant on the landscape.

” Our research study uses a clear predictive test to examine 2 opposing hypotheses about large animals in ancient and modern-day tundra environments: that the animals disappeared before the shrubs increased, or that the shrubs increased prior to the animals vanished,” stated Professor Mary Edwards of the University of Southampton who belonged to the study team.

Dr. Ali Monteath, the lead author from the Universities of Alberta and Southampton, adds “The outcomes support the idea that at the end of the last ice age a major shift to warmer and wetter conditions changed the landscape in a way that was extremely unfavorable to the animals, consisting of mammoths”.

The findings suggest that climate change was the primary controller of northern communities and that the big herbivores were unable to maintain their environment as the shrubs spread. “While people might have intensified population decreases, our outcomes recommend climate-driven vegetation modification was the main factor the mammals disappeared,” included Professor Edwards.

Going back to the idea of rewilding the North with big mammals that are presently missing from the area, the research study group concludes that this would probably not transform the greenery over big areas and so do little to curtail release of carbon from the Arctic permafrost.

Study co-author Professor Duane Froese of the University of Alberta stated, “Rewilding experiments at the scale of regional paddocks, as has been provided for example at Pleistocene Park (NE Siberia), show that megaherbivores can alter their environment, drive modifications in vegetation and even cool soil temperature level, however these animal densities are much higher than we would expect for Pleistocene ecosystems. Our research study reveals that the impact of megafauna grazing is little at sub-continental scales even with the presence of mammoths, and environment, once again, is the primary driver of these systems.”

Benjamin Gaglioti of the University of Alaska-Fairbanks added “The hypothesis that reestablishing megafauna will prevent or slow warming-driven permafrost thaw and plant life change in the Arctic has been bolstered by the idea that Pleistocene megafauna were important in keeping ice age communities. In contrast to this forecast, our outcomes reveal that high-latitude ecosystems reacted sensitively to past warming occasions, despite the fact that megafauna were plentiful on the landscape. These results lend support to the hypothesis that reintroducing megafauna today will do little to desensitize high latitude environments to human driven warming.”

Referral: “Late Pleistocene shrub expansion preceded megafauna turnover and extinctions in eastern Beringia” 20 December 2021, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.DOI: 10.1073/ pnas.2107977118.