1995– 2020

A sensor installed on the International Space Station is yielding fresh insights on the international circulation of lightning.

Given that the dawn of humanity, lightning has given both interest and awe. Though lots of flashes are crackling at any minute somewhere on Earth, these short electrical discharges– usually lasting less 30 split seconds– stay uncommonly challenging to study.

However, satellites have actually done much to deepen our understanding of lightning in recent years. Sensors in space have actually provided top quality observations of lightning flashes given that the 1990s, making it possible for atmospheric scientists to quantify and map the international circulation of lightning.

Earlier lightning activity maps assigned lightning flashes a single coordinate on a map. “Our analysis accounts for the reality that lightning bolts can spread horizontally, not simply vertically from clouds to the ground,” explained Michael Peterson of Los Alamos National Laboratory. “One way to think about this brand-new meteorology is that it tells us the frequency that an observer can anticipate lightning to be visible overhead– regardless of where the flash started or ended.”

While scientists are still in the process of harmonizing the various data records, they are optimistic that satellite data will show useful for identifying trends in lightning activity. By contributing to the production of nitrogen dioxide, a greenhouse gas, lightning is also a direct contributor to worldwide warming.

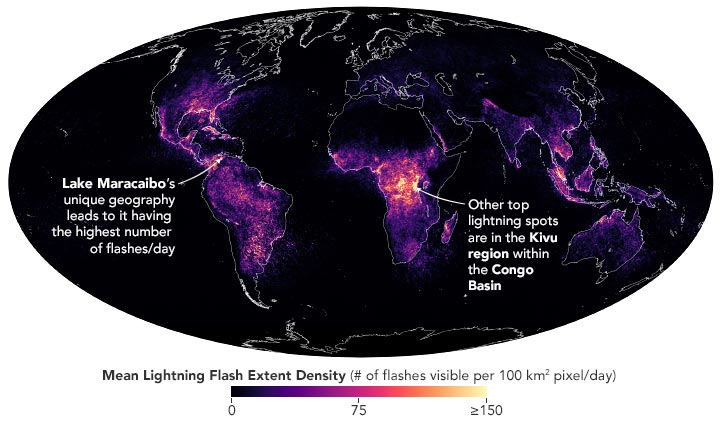

The new method does alter some details of how we comprehend lightning, the total patterns remain similar to in the past. With a typical flash rate of 389 per day, Lake Maracaibo in northern Venezuela (revealed above) has the highest flash degree density worldwide. That regions special location fuels weather condition patterns that make it a magnet for thunderstorms and lightning. The location along Lake Kivu, on the border of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, is a close 2nd with approximately 368 flashes daily.

While scientists are still in the process of harmonizing the various information records, they are optimistic that satellite information will show helpful for determining trends in lightning activity. By contributing to the production of nitrogen dioxide, a greenhouse gas, lightning is also a direct factor to international warming.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, utilizing information from Peterson, et al. (2021 ). Photograph by NASA.

One of the first worldwide maps of lightning activity was published in 2001 with data from the Optical Transient Detector ( OTD) on the industrial OrbView-1 satellite and the Lightning Image Sensor ( LIS) on NASAs TRMM satellite. Two years later, a 2nd LIS installed on the International Space Station (ISS) is contributing to long-term records and making more recent, better maps of global lightning activity.

The map above draws on observations from multiple sensors– the ISS LIS, the TRMM LIS, and OTD. The TRMM LIS gathered data between 1997 and 2015; OTD was operational between 1995 and 2000; and ISS LIS has been flying because 2017.

” What is significant and new about the ISS LIS is that it offers us observations that are significantly further north and south than we obtained from TRMM,” described Patrick Gatlin, a climatic researcher at NASA Marshall. “ISS LIS observations encompass latitudes approximately 55 North and 55 South, well into Canada and Patagonia.” Earlier worldwide lightning maps made use of TRMM LIS observations that were limited to the tropics. (Researchers usually utilize older, lower quality information from OTD to fill spaces in high-latitude locations).

” One of the amazing aspects of having ISS LIS information is that were beginning to be able to compare what is occurring with lightning now to what we saw in the 1990s with OTD, and with what we saw in the 2000s and 2010s with TRMM LIS,” said Tim Lang, an atmospheric scientist at NASA Marshall. “The satellites also have a built-in advantage over ground-based networks because we do not have gaps in the network and we have measurements over the oceans.”

Earlier lightning activity maps appointed lightning flashes a single coordinate on a map. “One way to believe about this new climatology is that it tells us the frequency that an observer can anticipate lightning to be visible overhead– regardless of where the flash ended or began.”

“Some lightning flashes– we call them megaflashes– actually propagate for extremely long horizontal ranges, often for numerous kilometers,” Peterson added. The longest lightning bolt ever tape-recorded covered 709 kilometers (440 miles) as it crackled through skies over Argentina and Brazil for 11 seconds in 2018.