In a new research study, Neil Hammerschlag, Ph.D., and colleagues utilized several techniques to assess the effects of ocean warming on tiger shark movements in the Western North Atlantic. Credit: Bianca Rangel

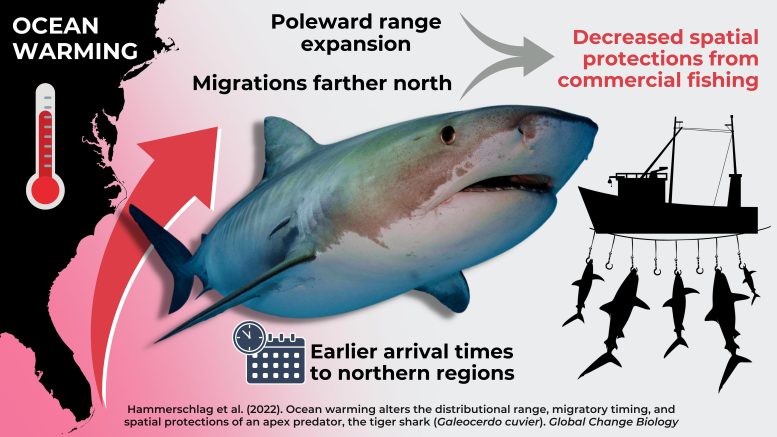

A brand-new research study led by researchers at the University of Miami (UM) Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science revealed that the areas and timing of tiger shark motion in the western North Atlantic Ocean have altered from rising ocean temperatures. These climate-driven changes have subsequently shifted tiger shark motions beyond secured areas, leaving the sharks more susceptible to industrial fishing.

The movements of tiger sharks, (Galeocerdo cuvier) the largest cold-blooded peak predator in warm-temperate and tropical seas, are constrained by the requirement to remain in warm waters. While waters off the U.S. northeast shoreline have actually historically been too cold for tiger sharks, temperatures have actually warmed significantly over the last few years making them suitable for the tiger shark.

” Tiger shark yearly migrations have actually expanded poleward, paralleling increasing water temperatures,” said Neil Hammerschlag, director of the UM Shark Research and Conservation Program and lead author of the research study. “These outcomes have effects for tiger shark preservation, because shifts in their movements beyond marine secured locations may leave them more vulnerable to business fishing.”

Hammerschlag and the research study group discovered these climate-driven modifications by evaluating 9 years of tracking information from satellite-tagged tiger sharks, integrated with almost forty years of conventional tag and regain info supplied by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Cooperative Shark Tagging Program and satellite obtained sea-surface temperature data.

The study found that during the last decade, when ocean temperatures were the warmest on record, for every single one-degree Celsius increase in water temperatures above average, tiger shark migrations extended further poleward by roughly 250 miles (over 400 kilometers) and sharks likewise migrated about 14 days earlier to waters off the U.S. northeastern coast.

The results might have greater community implications. “Given their role as apex predators, these modifications to tiger shark movements may alter predator-prey interactions, resulting in ecological imbalances, and more regular encounters with humans,” stated Hammerschlag.

Reference: “Ocean warming modifies the distributional range, migratory timing, and spatial protections of a pinnacle predator, the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier)” 13 January 2022, Global Change Biology.DOI: 10.1111/ gcb.16045.

The research studys authors include: Neil Hammerschlag, Laura McDonnell, Mitchell Rider, Ben Kirtman from the UM Rosenstiel School; Garrett Street and Melanie Boudreau from Mississippi State University; Elliott Hazen, Lisa Natanson, Camilla McCandless from NOAA Fisheries; Austin J. Gallagher from Beneath the Waves; and Malin Pinsky from Rutgers University.

The Batchelor Foundation, Disney Conservation Fund, Wells Fargo, Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation, the Herbert W. Hoover Foundation, the International Seakeepers Society, Oceana, Hoff Productions for National Geographic, and the West Coast Inland Navigation District supplied assistance for the research study.