2019– 2020

Heat and dry spell exacerbated fire season in 2020, however cattle grazing and other human activities likewise primed the region to burn.

Among the worlds largest freshwater wetlands– the Pantanal– spreads throughout a bowl-shaped plain where Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay meet. Throughout the rainy season in a lot of years, floodwater drains pipes from several swollen South American rivers into this huge inland delta, replenishing swamps and marshes. The area is home to countless plant and animal types, consisting of endangered and rare jaguars, hyacinth macaws, and huge river otters.

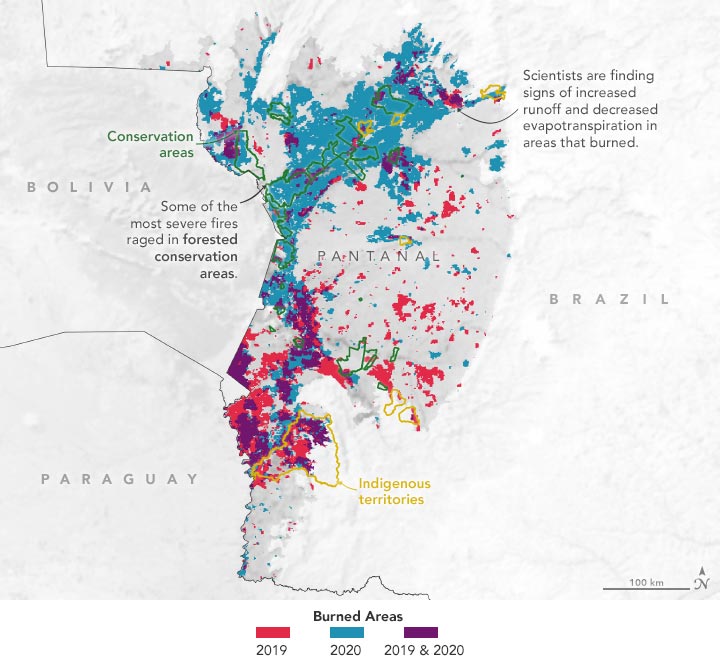

However in both 2019 and 2020, with the region grasped by extreme drought, those revitalizing floodwaters never came. Come June and July, fires did rather. They burned sporadically at first, but by August and September, they raged with such ferocity that they left vast swaths of the Pantanal blackened. The fires blanketed cities far and wide with a pall of smoke. The burning was extreme in 2019, charring approximately 16,000 square kilometers (6,200 square miles). In 2020, the scale was catastrophic, burning one-third of the whole biome. An exceptional 39,000 square kilometers (15,000 square miles) burned in 2020, an area about the size of Switzerland.

In the immediate consequences of the 2020 fires, the easy description for the comprehensive fires was that unusually dry, hot weather had actually sustained them.” It is certainly real that severe heat and drought in 2020 worsened the fires, however thats not the whole story,” stated Sujay Kumar, a hydrologist at NASAs Goddard Space Flight. We even saw an extremely particular pattern of fire activity that suggests people enabled or even encouraged fires to burn in forested areas.”

” With over 52 percent of natural locations burned compared to only 6 percent of regions with high-cattle density, it is clear that natural, not human-dominated landscapes were most affected by the 2020 fires,” said research study co-author Niels Andela, a remote sensing scientist at Cardiff University. Lightning often fires up fires in the Pantanal, but these fires tend to be little, causing simply 5 percent of the overall burnt area on average.

In the immediate aftermath of the 2020 fires, the easy description for the extensive fires was that abnormally dry, hot weather had actually sustained them. However a new study led by NASA scientists suggests that human activity played a critical function in intensifying them. The study was released in Scientific Reports in January 2022.

September 6, 2020

” It is definitely true that severe heat and drought in 2020 intensified the fires, but thats not the whole story,” said Sujay Kumar, a hydrologist at NASAs Goddard Space Flight. “It is likewise clear, based on a variety of data, that these fires would not have occurred in the absence of human activity. We even saw a very specific pattern of fire activity that suggests individuals enabled and even motivated fires to burn in forested locations.”

Together with coworkers from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Cardiff University, and NASAs Marshall Space Flight Center, Kumar analyzed land cover and burned location data from NASAs Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), rainfall information from the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) objective, and soil wetness information from the Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellite. The team also considered the density of livestock operations.

” With over 52 percent of natural areas burned compared to just 6 percent of areas with high-cattle density, it is clear that natural, not human-dominated landscapes were most impacted by the 2020 fires,” said study co-author Niels Andela, a remote noticing scientist at Cardiff University. “The sensitivity of natural landscapes to fire-driven destruction has been a concern across the southern Amazon for years. With this research, we provide the very first large-scale evidence that the exact same mechanisms might apply across the tropics, consisting of in the Pantanal.”

August 27, 2020

February 20, 2000

February 20, 2000

The researchers also tried to find signs that the fires may have altered the environment in long lasting ways. They took a look at the areas hydrology– how water streams throughout the landscape– utilizing a data assimilation model called the Land Information System. The LIS integrates satellite- and ground-based observations with modeling methods that define land surface conditions.

” Several months after the fire, we saw clear proof of decreased evapotranspiration and more surface runoff, patterns that can accelerate or trigger desertification,” stated NASA hydrologist Augusto Getirana, among the research studys co-authors. Scorched soils with less plant life can suggest less rainfall being taken in by plants, more water and sediment running the land into streams, and less moisture exchange with the air above. “All of this amounts to increased land destruction.”

Modifications like these might trigger brand-new challenges for the areas wildlife, which have currently been struck hard by the burning and might have a hard time under new ecological conditions. One group of biologists that surveyed the Pantanal not long after the fires approximated that at least 17 million vertebrates were likely killed, including millions of snakes, birds, and rodents.

While conservation locations and indigenous territories have been set up to limit development in parts of the Pantanal, the human finger print on the landscape is large and growing. Another current research study approximated that the quantity of the Pantanal devoted to farming– typically livestock pasture– has actually increased by 3.5 percent per year because the mid-1980s. Some 3.8 million cattle are now spread out among 3,000 farms, according to one quote. Ranchers in the Pantanal routinely use fire to preserve pastures and often to clear locations to develop new pastures.

February 20, 2000– February 21, 2021

The growth of pasture appears in the set of natural-color Landsat images above, which reveal part of Mato Grosso do Sul near Morrinho. While the location had very little advancement and was mostly natural in 2000 (left image), much of it had actually been transformed into pasture by 2021 (right image). Cleanings for pastures appear as light green and brown rectangular shapes. Surface area water is dark blue.

” As in other parts of the Amazon Basin, we are basically seeing an arc of deforestation and land cover modification spread out along the Upper Paraguay River,” said Renata Libonati of Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. “There is little that is natural about these fires. Some were most likely lit purposefully to keep pastures on or near cattle ranches. Others were unexpected but related to human activities– things like campfires, burning garbage, electrical wires, automobile, searching, and beekeeping.” Lightning often sparks fires in the Pantanal, but these fires tend to be small, triggering just 5 percent of the total burnt area typically. Also, lightning-triggered fires normally burn in the austral summertime (December-February) not the winter (June-August).

Further encroachment, combined with environment change and fires, is worrisome to Libonati. “We understand that compound drought-heatwaves like we saw in 2020 are most likely to become more typical in the future due to environment change,” said Libonati. “Its become obvious that were going to need long-lasting management techniques to safeguard the Pantanal from future fire outbreaks like this.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using information from Kumar, Sujay, et al. (2022) and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey