It discovers that average tree death rates in these woods have more than doubled over the last 4 years. Researchers found that trees are living around half as long, which is consistent throughout types and websites throughout the region. Northeast Australias relict tropical rain forests, one of the earliest and most isolated rain forests in the world. Tree death rates have actually markedly increased across species in northeast Australias tropical rain forests, threatening the important environment mitigation and other functions of these ecosystems. The likely driving aspect we determine, the increasing drying power of the environment triggered by worldwide warming, suggests comparable increases in tree death rates might be taking place throughout the worlds tropical forests.

According to a brand-new study, trees are living about half as long as they previously did. This trend was discovered to be extensive throughout types and places across the region.

According to new research study, environment modification may have triggered jungle trees to pass away quicker starting in the 1980s

The results of a long-lasting worldwide study published in Nature on May 18th, 2022 show that tropical trees in Australias rain forests have actually been dying at a rate twice as high as before considering that the 1980s, probably due to environment effects. According to this study, as the drying effect of the environment has increased due to worldwide warming, the mortality rates of tropical trees have actually doubled over the last 35 years.

Wear and tear of such forests decreases biomass and carbon storage, making it more difficult to follow the Paris Agreements requirement to keep global peak temperature levels well below the objective of 2 ° C. The existing study, headed by professionals from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and Oxford University, as well as the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD), has actually evaluated really substantial information records from Australias rain forests.

It finds that average tree death rates in these woods have more than doubled over the last 4 years. Researchers found that trees are living around half as long, which corresponds across types and websites across the area. According to the researchers, the results might be observed as far back as the 1980s.

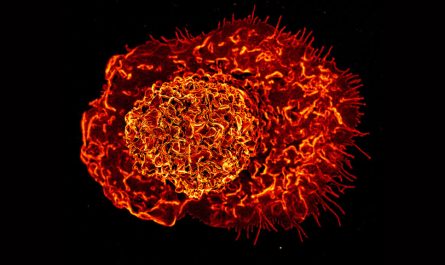

Northeast Australias relict tropical rain forests, one of the oldest and most isolated rain forests on the planet. Tree death rates have actually considerably increased throughout species in northeast Australias tropical rain forests, threatening the important environment mitigation and other functions of these environments. Credit: Alexander Schenkin

Dr. David Bauman, a tropical forest ecologist at Smithsonian, Oxford, and IRD, and lead author of the research study keeps, “It was a shock to discover such a marked boost in tree mortality, let alone a pattern constant throughout the variety of websites and species we studied. A continual doubling of death threat would imply the carbon saved in trees returns two times as fast to the environment.”

Dr. Sean McMahon, Senior Research Scientist at Smithsonian and senior author of the research study explains, “Many decades of information are needed to spot long-term modifications in long-lived organisms, and the signal of a change can be overwhelmed by the noise of many processes.”

Drs Bauman and McMahon stress, “One amazing outcome from this research study is that, not just do we detect an increase in mortality, however this increase appears to have started in the 1980s, suggesting the Earths natural systems may have been reacting to changing climate for years.”

Oxford Professor Yadvinder Malhi, a research study co-author, mentions, In recent years the effects of climate change on the corals of the Great Barrier Reef have become popular.

” Our work reveals if you look shoreward from the Reef, Australias well-known rainforests are also changing quickly. The likely driving element we recognize, the increasing drying power of the atmosphere triggered by global warming, suggests comparable increases in tree death rates might be taking place across the worlds tropical forests. If that is the case, tropical forests may soon become carbon sources, and the obstacle of limiting international warming well listed below 2 ° C ends up being both more urgent and more difficult.”

Susan Laurance, Professor of Tropical Ecology at James Cook University, adds, “Long-term datasets like this one are really important and extremely unusual for studying forest changes in response to climate modification. This is since rain forest trees can have such long lives and likewise that tree death is not always immediate.”

Recent studies in Amazonia have also suggested tropical tree death rates are increasing, hence compromising the carbon sink. But the factor is unclear.

Intact tropical rainforests are major stores of carbon and till now have actually been carbon sinks, functioning as moderate brakes on the rate of climate change by taking in around 12% of human-caused carbon dioxide emissions.

Examining the climate series of the tree species showing the highest death rates, the group suggests the primary climate chauffeur is the increased drying power of the atmosphere. As the environment warms, it draws more wetness from plants, leading to increased water stress in trees and eventually increased danger of death.

When the scientists crunched the numbers, it further revealed the loss of biomass from this death boost over the previous decades has not been offset by biomass gains from tree development and recruitment of brand-new trees. This indicates the death boost has actually translated into a net decline in the capacity of these forests to offset carbon emissions.

The research group included associates from Oxford University, James Cook University (Australia), and other organizations (UK, France, USA, Peru).

Recommendation: “Tropical tree death has actually increased with increasing climatic water stress” by David Bauman, Claire Fortunel, Guillaume Delhaye, Yadvinder Malhi, Lucas A. Cernusak, Lisa Patrick Bentley, Sami W. Rifai, Jesús Aguirre-Gutiérrez, Imma Oliveras Menor, Oliver L. Phillips, Brandon E. McNellis, Matt Bradford, Susan G. W. Laurance, Michael F. Hutchinson, Raymond Dempsey, Paul E. Santos-Andrade, Hugo R. Ninantay-Rivera, Jimmy R. Chambi Paucar, and Sean M. McMahon, 18 May 2022, Nature.DOI: 10.1038/ s41586-022-04737-7.