Stanleycaris hirpex. Credit: Sabrina Cappelli © Royal Ontario Museum

An ancient radiodont predator with three eyes exposes crucial info about the evolution of the arthropod body plan.

New research study based upon a cache of fossils that contains the brain and nervous system of a half-billion-year-old marine predator from the Burgess Shale called Stanleycaris has actually been revealed by the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). Belonging to an ancient, extinct offshoot of the arthropod evolutionary tree called Radiodonta, Stanleycaris is distantly related to modern-day bugs and spiders. These outcomes shed light on the advancement of the arthropod brain, head, and vision structure.

” The details are so clear its as if we were looking at an animal that passed away the other day.”

About the Burgess Shale

For this research study, Moysiuk and Caron studied a formerly unpublished collection of 268 specimens of Stanleycaris. The fossils were primarily collected in the 1980s and 90s from rock layers above the well-known Walcott Quarry website of the Burgess Shale in Yoho National Park, B.C., Canada, and belong to the extensive collection of Burgess Shale fossils housed at ROM.

The Burgess Shale fossil sites lie within Yoho and Kootenay National Parks and are managed by Parks Canada. Parks Canada is proud to deal with leading scientific scientists to broaden knowledge and understanding of this crucial period of earth history and to share these sites with the world through award-winning guided walkings. The Burgess Shale was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 due to its impressive universal worth and is now part of the bigger Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site.

Fossils of Stanleycaris can be seen by the public in the new Burgess Shale fossil display screen in the Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life at ROM.

Referral: “A three-eyed radiodont with fossilized neuroanatomy notifies the origin of the arthropod head and segmentation” by Joseph Moysiuk and Jean-Bernard Caron, 8 July 2022, Current Biology.DOI: 10.1016/ j.cub.2022.06.027.

Major research funding assistance came from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, through a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship to Moysiuk and a Discovery Grant (no. 341944) to Caron.

Fossil specimen of Stanleycaris hirpex. Dark material inside the head is the remains of anxious tissue, specimen ROMIP 65674.2. Credit: Photo by Jean-Bernard Caron © Royal Ontario Museum

— Joseph Moysiuk

The findings were announced in the term paper, “A three-eyed radiodont with fossilized neuroanatomy notifies the origin of the arthropod head and division,” published on July 5, 2022, in the journal Current Biology.

Pair of fossil specimens of Stanleycaris hirpex, specimen ROMIP 65674.1-2. Credit: Photo by Jean-Bernard Caron, © Royal Ontario Museum

What has actually scientists most excited is whats inside Stanleycaris head. The remains of the brain and nerves are still preserved after 506 million years in 84 of the fossils.

” While fossilized brains from the Cambrian Period arent new, this discovery stands out for the amazing quality of conservation and the big number of specimens,” said Joseph Moysiuk, lead author of the research study and a University of Toronto (U of T) PhD Candidate in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, based at the Royal Ontario Museum. “We can even construct out great information such as visual processing centers serving the large eyes and traces of nerves going into the appendages. The details are so clear its as if we were taking a look at an animal that died yesterday.”

Turntable animation of Stanleycaris hirpex, including transparency to reveal internal organs. Credit: Animation by Sabrina Cappelli © Royal Ontario Museum

The new fossils expose that the brain of Stanleycaris was composed of two sections, the protocerebrum, gotten in touch with the eyes, and the deutocerebrum, linked with the frontal claws.

” We conclude that a two-segmented head and brain has deep roots in the arthropod lineage and that its evolution most likely preceded the three-segmented brain that defines all living members of this diverse animal phylum,” added Moysiuk.

In contemporary arthropods like bugs, the brain consists of protocerebrum, tritocerebrum, and deutocerebrum. While the difference in a section may not sound game-changing, it in fact has extreme scientific implications. Considering that duplicated copies of many arthropod organs can be discovered in their segmented bodies, determining how sectors line up in between different types is essential to comprehending how these structures diversified across the group.

” These fossils resemble a Rosetta Stone, helping to connect characteristics in radiodonts and other early fossil arthropods with their equivalents in surviving groups.”

Restoration of a set of Stanleycaris hirpex; upper individual has transparency of the outside increased to reveal internal organs. Worried system is shown in light beige, digestive system in dark red. Credit: Illustration by Sabrina Cappelli © Royal Ontario Museum

In addition to its pair of stalked eyes, Stanleycaris had a large central eye at the front of its head, a function never ever before seen in a radiodont. “The existence of a huge third eye in Stanleycaris was unexpected. It highlights that these animals were much more bizarre-looking than we thought, however likewise shows us that the earliest arthropods had currently evolved a range of complex visual systems like many of their modern kin” stated Dr. Jean-Bernard Caron, ROMs Richard Ivey Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology, and Moysiuks PhD manager. “Since a lot of radiodonts are just known from scattered pieces and bits, this discovery is a crucial jump forward in comprehending what they looked like and how they lived,” included Caron, who is likewise an Associate Professor at the U of T, in Ecology & & Evolution and Earth Sciences.

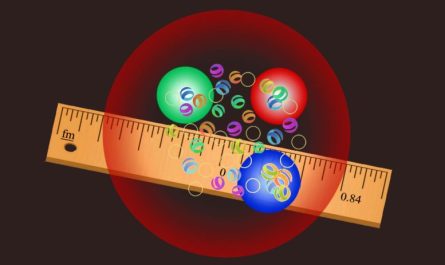

Paper summary, revealing the interpretation of the nerve system from fossils of Stanleycaris and ramifications for understanding the evolution of the arthropod brain. The brain is represented in red and the nerve cables in purple. Credit: Photo by Jean-Bernard Caron © Royal Ontario Museum

In the Cambrian Period, radiodonts consisted of some of the biggest animals around, with the famous “strange wonder” Anomalocaris reaching up to at least 1 meter in length. At no more than 20 cm long, Stanleycaris was little for its group, however at a time when most animals grew no bigger than a human finger, it would have been an impressive predator. Stanleycaris sophisticated sensory and worried systems would have enabled it to efficiently choose out little prey in the gloom.

Restoration of Stanleycaris hirpex. Credit: Art by Sabrina Cappelli © Royal Ontario Museum

With large compound eyes, a formidable-looking circular mouth lined with teeth, frontal claws with an impressive selection of spines, and a versatile, segmented body with a series of swimming flaps along its sides, Stanleycaris would have been the things of headaches for any little bottom occupant unfortunate adequate to cross its course.

New research study based on a cache of fossils that consists of the brain and nervous system of a half-billion-year-old marine predator from the Burgess Shale called Stanleycaris has been revealed by the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). Belonging to an ancient, extinct offshoot of the arthropod evolutionary tree called Radiodonta, Stanleycaris is distantly associated to modern-day pests and spiders. Paper summary, showing the interpretation of the worried system from fossils of Stanleycaris and ramifications for understanding the evolution of the arthropod brain. Fossil specimen of Stanleycaris hirpex. Fossil specimen of Stanleycaris hirpex.

Fossil specimen of Stanleycaris hirpex. Dark product inside the head is the remains of nervous tissue, specimen ROMIP 65674.1. Credit: Photo by Jean-Bernard Caron © Royal Ontario Museum