The largest study on aging and life-span to date, carried out by a global group of 114 researchers and directed by Penn State and Northeastern Illinois University, has recently been released. The scientists discovered numerous things, consisting of for the very first time, that salamanders, crocodilians, and turtles had exceptionally sluggish aging rates and prolonged life expectancies for their sizes. The research group likewise found that protective phenotypes, such as the hard shells of the bulk of turtle species, lead to slower aging and, in particular situations, even to “minimal aging,” or the lack of biological aging.

Miller added, “Negligible aging means that if an animals opportunity of passing away in a year is 1% at age 10, if it is alive at 100 years, its opportunity of passing away is still 1%. By contrast, in adult women in the U.S., the threat of dying in a year is about 1 in 2,500 at age 10 and 1 in 24 at age 80.

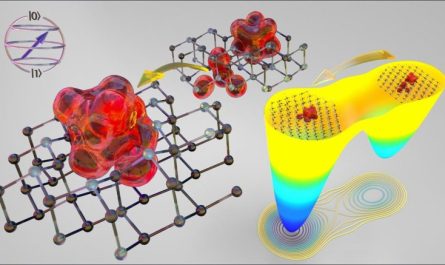

In their research study, the scientists used mark-recapture information, in which animals are taken, tagged, launched back into the wild, and then enjoyed, in conjunction with relative phylogenetic methods, which permit examination of organisms advancement. Their purpose was to compare ectotherm aging and life-span in the wild to endotherms (warm-blooded animals) and examine earlier presumptions about aging, such as way of body temperature level control and the existence or absence of protective physical features.

The face of a tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus). Credit: Sarah Lamar

Miller explained that the thermoregulatory mode hypothesis suggests that ectotherms– since they need external temperature levels to regulate their body temperatures and, therefore, typically have lower metabolic process– age more slowly than endotherms, which internally produce their own heat and have greater metabolic process.

” People tend to believe, for instance, that mice age quickly due to the fact that they have high metabolisms, whereas turtles age gradually due to the fact that they have low metabolisms,” stated Miller.

The groups findings, however, expose that ectotherms aging rates and lifespans vary both well above and listed below the recognized aging rates for similar-sized endotherms, suggesting that the method an animal regulates its temperature level– warm-blooded versus cold-blooded– is not always indicative of its aging rate or life expectancy.

” We didnt find assistance for the idea that a lower metabolic rate suggests ectotherms are aging slower,” stated Miller. “That relationship was only real for turtles, which suggests that turtles are unique among ectotherms.”

The protective phenotypes hypothesis suggests that animals with physical or chemical characteristics that confer defense– such as armor, spinal columns, shells, or venom– have slower aging and higher longevity. The team recorded that these protective traits do, undoubtedly, make it possible for animals to age more slowly and, when it comes to physical defense, live a lot longer for their size than those without protective phenotypes.

” It could be that their modified morphology with hard shells offers protection and has contributed to the development of their biography, including negligible aging– or absence of market aging– and remarkable durability,” said Anne Bronikowski, co-senior author and professor of integrative biology, Michigan State.

Therefore, theyre more most likely to live longer, and that applies pressure to age more slowly. We discovered the biggest assistance for the protective phenotype hypothesis in turtles.

Remarkably, the group observed minimal aging in a minimum of one species in each of the ectotherm groups, including frogs and toads, turtles, and crocodilians.

An Iberian tree frog (Hyla molleri). Credit: Iñigo Martínez-Solano

” It sounds dramatic to say that they do not age at all, however generally their possibility of dying does not change with age once theyre previous recreation,” said Reinke.

Miller added, “Negligible aging indicates that if an animals chance of passing away in a year is 1% at age 10, if it lives at 100 years, its opportunity of dying is still 1%. By contrast, in adult women in the U.S., the risk of passing away in a year is about 1 in 2,500 at age 10 and 1 in 24 at age 80. When a species exhibits negligible senescence (degeneration), aging just doesnt occur.”

Because of the contributions of a large number of partners from throughout the world studying a large variety of species, Reinke noted that the groups unique research study was just possible.

” Being able to bring these authors together who have all done years and years of work studying their individual types is what made it possible for us to get these more dependable quotes of aging rate and durability that are based on population data instead of just individual animals,” she said.

Bronikowski added, “Understanding the relative landscape of aging across animals can expose versatile qualities that might prove worthy targets for biomedical research study associated to human aging.”

Referral: “Diverse aging rates in ectothermic tetrapods supply insights for the development of aging and durability” by Beth A. Reinke, Hugo Cayuela, Fredric J. Janzen, Jean-François Lemaître, Jean-Michel Gaillard, A. Michelle Lawing, John B. Iverson, Ditte G. Christiansen, Iñigo Martínez-Solano, Gregorio Sánchez-Montes, Jorge Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, Francis L. Rose, Nicola Nelson, Susan Keall, Alain J. Crivelli, Theodoros Nazirides, Annegret Grimm-Seyfarth, Klaus Henle, Emiliano Mori, Gaëtan Guiller, Rebecca Homan, Anthony Olivier, Erin Muths, Blake R. Hossack, Xavier Bonnet, David S. Pilliod, Marieke Lettink, Tony Whitaker, Benedikt R. Schmidt, Michael G. Gardner, Marc Cheylan, Françoise Poitevin, Ana Golubović, Ljiljana Tomović, Dragan Arsovski, Richard A. Griffiths, Jan W. Arntzen, Jean-Pierre Baron, Jean-François Le Galliard, Thomas Tully, Luca Luiselli, Massimo Capula, Lorenzo Rugiero, Rebecca McCaffery, Lisa A. Eby, Venetia Briggs-Gonzalez, Frank Mazzotti, David Pearson, Brad A. Lambert, David M. Green, Nathalie Jreidini, Claudio Angelini, Graham Pyke, Jean-Marc Thirion, Pierre Joly, Jean-Paul Léna, Anton D. Tucker, Col Limpus, Pauline Priol, Aurélien Besnard, Pauline Bernard, Kristin Stanford, Richard King, Justin Garwood, Jaime Bosch, Franco L. Souza, Jaime Bertoluci, Shirley Famelli, Kurt Grossenbacher, Omar Lenzi, Kathleen Matthews, Sylvain Boitaud, Deanna H. Olson, Tim S. Jessop, Graeme R. Gillespie, Jean Clobert, Murielle Richard, Andrés Valenzuela-Sánchez, Gary M. Fellers, Patrick M. Kleeman, Brian J. Halstead, Evan H. Campbell Grant, Phillip G. Byrne, Thierry Frétey, Bernard Le Garff, Pauline Levionnois, John C. Maerz, Julian Pichenot, Kurtuluş Olgun, Nazan Üzüm, Aziz Avcı, Claude Miaud, Johan Elmberg, Gregory P. Brown, Richard Shine, Nathan F. Bendik, Lisa ODonnell, Courtney L. Davis, Michael J. Lannoo, Rochelle M. Stiles, Robert M. Cox, Aaron M. Reedy, Daniel A. Warner, Eric Bonnaire, Kristine Grayson, Roberto Ramos-Targarona, Eyup Baskale, David Muñoz, John Measey, F. Andre de Villiers, Will Selman, Victor Ronget, Anne M. Bronikowski and David A. W. Miller, 23 June 2022, Science.DOI: 10.1126/ science.abm0151.

The research study was moneyed by the National Institutes of Health..

The research study team also found that protective phenotypes, like the hard shells of many turtle types, may delay the aging procedure and, in some scenarios, even stop biological aging.

The biggest study of its kind reveals that wild turtles age slowly, live long lives, and discovers numerous types that virtually do not age

The largest research study on aging and life expectancy to date, conducted by a global team of 114 researchers and directed by Penn State and Northeastern Illinois University, has recently been released. It consists of data gathered in the wild from 107 populations of 77 different types of amphibians and reptiles.

A photo of a painted turtle (Chrysemys picta), a widespread North American types of freshwater turtle. Credit: Beth A. Reinke, Northeastern Illinois University

The scientists discovered numerous things, consisting of for the very first time, that turtles, crocodilians, and salamanders had very sluggish aging rates and prolonged lifespans for their sizes. They recently released their results in the journal Science. The research study team likewise discovered that protective phenotypes, such as the difficult shells of the bulk of turtle species, cause slower aging and, in certain scenarios, even to “negligible aging,” or the absence of biological aging.

” Anecdotal evidence exists that some reptiles and amphibians age slowly and have long life-spans, but previously no one has actually studied this on a large scale throughout numerous species in the wild,” stated David Miller, senior author and associate teacher of wildlife population ecology, Penn State. “If we can understand what allows some animals to age more gradually, we can much better comprehend aging in humans, and we can likewise notify conservation strategies for reptiles and amphibians, numerous of which are threatened or endangered.”