The signals can be an early sign of an establishing El Niño, and were spotted by the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich sea level satellite. When they form at the equator, Kelvin waves bring warm water, which is associated with higher sea levels, from the western Pacific to the eastern Pacific. Sea level data from the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite on April 24 shows reasonably higher (revealed in white and red) and warmer ocean water at the west and the equator coast of South America. By April 24, Kelvin waves had actually piled up warmer water and greater sea levels (shown in white and red) off the coasts of Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. Satellites like Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich can identify Kelvin waves with a radar altimeter, which uses microwave signals to measure the height of the oceans surface area.

This animation shows a series of waves, called Kelvin waves, moving warm water throughout the equatorial Pacific Ocean from west to east throughout March and April. The signals can be an early sign of an establishing El Niño, and were detected by the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich water level satellite. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Kelvin waves, a potential precursor of El Niño conditions in the ocean, are rolling throughout the equatorial Pacific towards the coast of South America.

Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite information shows early indications of a potential El Niño, a climate phenomenon known to disrupt global weather patterns. The information reveals Kelvin waves bring warmer water and higher water level across the Pacific, with prospective global weather impacts expected.

The most recent sea level data from the U.S.-European satellite Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich shows early signs of an establishing El Niño across the equatorial Pacific Ocean. The data shows Kelvin waves– which are roughly 2 to 4 inches (5 to 10 centimeters) high at the ocean surface and numerous miles wide– moving from west to east along the equator towards the west coast of South America.

When they form at the equator, Kelvin waves bring warm water, which is connected with higher water level, from the western Pacific to the eastern Pacific. A series of Kelvin waves beginning in spring is a popular precursor to an El Niño, a regular environment phenomenon that can impact weather patterns around the globe. It is identified by greater sea levels and warmer-than-average ocean temperature levels along the western coasts of the Americas.

Water broadens as it warms, so sea levels tend to be greater in locations with warmer water. El Niño is also related to a weakening of the trade winds. The condition can bring cooler, wetter conditions to the U.S. Southwest and drought to nations in the western Pacific, such as Indonesia and Australia.

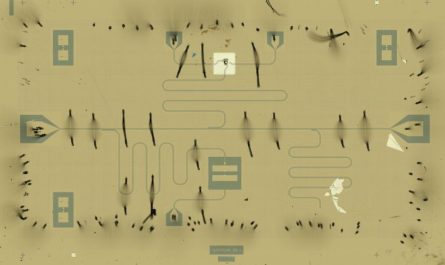

Sea level information from the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite on April 24 shows relatively higher (displayed in red and white) and warmer ocean water at the west and the equator coast of South America. Water broadens as it warms, so sea levels tend to be higher in locations with warmer water. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

By April 24, Kelvin waves had piled up warmer water and greater sea levels (shown in white and red) off the coasts of Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. Satellites like Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich can detect Kelvin waves with a radar altimeter, which uses microwave signals to measure the height of the oceans surface.

” Well be watching this El Niño like a hawk,” said Josh Willis, Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich project researcher at NASAs Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “If its a big one, the globe will see record warming, however here in the Southwest U.S. we might be taking a look at another wet winter season, right on the heels of the soaking we got last winter.”

Both the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the World Meteorological Organization have actually just recently reported increased opportunities that El Niño will develop by the end of the summer. Continued monitoring of ocean conditions in the Pacific by instruments and satellites such as Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich need to assist to clarify in the coming months how strong it might become.

” When we determine water level from area using satellite altimeters, we know not only the shape and height of water, but likewise its movement, like Kelvin and other waves,” said Nadya Vinogradova Shiffer, NASA program scientist and supervisor for Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich in Washington. “Ocean waves slosh heat around the world, bringing heat and wetness to our coasts and changing our weather condition.”

More About the Mission

Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich, named after previous NASA Earth Science Division Director Michael Freilich, is among two satellites that compose the Copernicus Sentinel-6/ Jason-CS (Continuity of Service) objective.

Sentinel-6/ Jason-CS was collectively established by ESA (European Space Agency), the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT), NASA, and NOAA, with financing assistance from the European Commission and technical assistance on efficiency from the French space firm CNES (Centre National dÉtudes Spatiales). Spacecraft tracking and control, as well as the processing of all the altimeter science information, is performed by EUMETSAT on behalf of the European Unions Copernicus program, with the assistance of all partner agencies.

JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, contributed 3 science instruments for each Sentinel-6 satellite: the Advanced Microwave Radiometer, the Global Navigation Satellite System– Radio Occultation, and the Laser Retroreflector Array. NASA also contributed launch services, ground systems supporting operation of the NASA science instruments, the science information processors for two of these instruments, and assistance for the U.S. members of the international Ocean Surface Topography Science Team.