The scientists recommend that the two populations be thought about separately for preservation functions, with separate however coordinated preservation efforts to handle each population.

” Interbreeding amongst various populations results in the exchange of genetic info– typically called gene flow– and is normally considered to be helpful because it can improve total hereditary diversity and help buffer small populations versus disease and other threats,” said Lan Wu-Cavener, assistant research study professor of biology and a member of the research team. We originally thought that one population was founded and then some individuals crossed over to the other side of the rift to establish the 2nd population.” Taken together, these results suggest that populations of giraffes on each side of the rift are genetically distinct, with each population having less hereditary diversity than if they were one, larger interconnected population,” stated Cavener. “Theres a lot we dont know about how giraffes mate, for example do only a couple of males effectively reproduce in a regional population over numerous years or do several males reproduce in that population?

Penn State researchers found Masai giraffe populations divided by East Africas Great Rift Valley have not interbred for centuries. This, together with significant inbreeding and a 50% decrease over 30 years, recommends they are more threatened than formerly thought. Unique but coordinated conservation efforts for each population are recommended.

Giraffe populations separated by Great Rift Valley in eastern Africa are genetically unique, recommending that conservation efforts ought to be considered separately for each population.

Giraffes in eastern Africa might be even more endangered than previously believed. A brand-new research study led by researchers at Penn State reveals that populations of Masai giraffes separated geographically by the Great Rift Valley have not interbred– or exchanged hereditary product– in more than a thousand years, and in some cases hundreds of countless years. The scientists suggest that the two populations be considered separately for preservation purposes, with separate but collaborated conservation efforts to manage each population.

Populations of giraffes have actually declined rapidly in the last thirty years, with less than 100,000 people staying around the world. Numbers of Masai giraffes, a types found in Tanzania and southern Kenya that are thought about endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) have actually declined by about 50% in this period due to unlawful hunting and other human activities that intrude on their environment, with only about 35,000 people remaining.

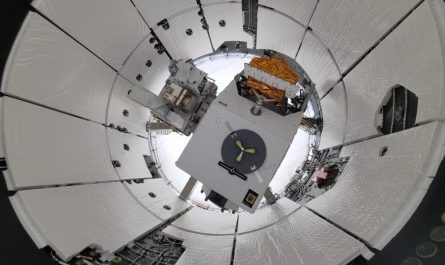

A brand-new research study by researchers at Penn State reveals that populations of giraffes separated geographically by the Great Rift Valley have actually not exchanged hereditary product in more than a thousand years, raising preservation concerns. Credit: Sonja-Metzger

” The environment of Masai giraffes is highly fragmented, in part due to the fast growth of the human population in east Africa in the last 30 years and the ensuing loss of wildlife habitats,” said Douglas Cavener, Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck Distinguished Chair in Evolutionary Genetics and teacher of biology at Penn State and leader of the research group. “Additionally, the Great Rift Valley lowers through East Africa, and the steep slopes of its cliffs are powerful barriers to wildlife migration. We looked at the genomes of 100 Masai giraffes to identify if populations on either side of the rift have actually crossed over to breed with each other in the current past, which has crucial ramifications for conservation.”

According to the scientists, giraffes are infamously bad climbers. Using high-resolution satellite information, they discovered only two locations where the angle of the rifts slopes was shallow enough for giraffes to possibly climb over, however there are no reports of them actually doing so.

” Interbreeding among different populations results in the exchange of genetic details– frequently called gene flow– and is normally thought about to be advantageous since it can enhance overall hereditary diversity and aid buffer little populations versus disease and other risks,” stated Lan Wu-Cavener, assistant research study teacher of biology and a member of the research group. “To comprehend prospective gene flow throughout the rift, we sequenced the more than 2 billion base pairs that make up entire nuclear genome along with the more than 16,000 base pairs that make up the whole mitochondrial genome. This complex information presented a variety of computational and information storage challenges for our little team, however utilizing the entire genome rather of a small portion enabled us to definitively investigate the level of gene circulation among these populations.”

The researchers determined numerous blocks of genes within the mitochondrial genome that are typically inherited together– which researchers call haplotypes– throughout the two populations and carried out a network analysis based on patterns of similarity throughout those haplotypes. They discovered that giraffes on the east side of the rift had no overlapping haplotypes with giraffes on the west side of the rift, which recommends that females have not moved throughout the rift to reproduce in the previous 250,000-300,000 years.

” Female-mediated gene flow between the two populations has actually not happened in hundreds of countless years, or most likely ever,” said Cavener. “This raised a brand-new question that we had not anticipated about the origin of these populations. We originally believed that one population was established and after that some people crossed over to the opposite of the rift to develop the 2nd population. But we now think that the 2 populations were founded separately more than 200,000 years ago.”

Analysis of the nuclear genome suggests that gene circulation through the motion of males may have happened as just recently as a thousand years earlier. When and why this gene circulation might have stopped, the researchers prepare to take samples from additional animals from both populations to better understand.

” Taken together, these results recommend that populations of giraffes on each side of the rift are genetically unique, with each population having less genetic diversity than if they were one, bigger interconnected population,” said Cavener. “There are extremely little prospects of giraffes crossing over the rift by themselves, and translocation is highly unwise with giraffes. This recommends that Masai giraffes are more threatened than we formerly believed, and that conservation efforts for each population should be considered in an independent however collaborated fashion. We hope that the Kenyan and tanzanian governments will increase the protection of Masai giraffes and their environments, specifically given the recent increase in giraffe poaching in the location.”

The researchers also found amazingly high indications of inbreeding– a procedure that decreases hereditary diversity and total physical fitness of the population– on both the west and east side of the rift. The researchers plan to continue to study populations of Masai giraffes on both sides of the rift, consisting of those that are especially isolated, to better understand any threat faced due to inbreeding. They also plan to investigate how giraffes move in between groups on the east side of the rift, where the habitat is particularly fragmented, to much better comprehend how to focus on preservation efforts to keep connectivity in between them.

” We would also like to use genetics to clarify parental and sibling relationships in Masai giraffes,” stated Cavener. “Theres a lot we do not learn about how giraffes mate, for instance do only a couple of males effectively breed in a regional population over lots of years or do a number of males reproduce because population? These concerns are seriously crucial to estimating the real reproducing population of the populations and will continue to direct our efforts to protect and save these marvelous and charismatic animals.”

Reference: “Genetic proof of population neighborhood amongst Masai giraffes separated by the Gregory Rift Valley in Tanzania” 12 June 2023, Ecology and Evolution.DOI: 10.1002/ ECE3.10160.

In addition to Cavener and Wu-Cavener, the research study group at Penn State includes very first author George Lohay, postdoctoral scholar who gathered the biological samples from wild giraffe in Tanzania; Associate Research Professor of Biology Derek Lee and academic affiliate in biology Monica Bond, whose work over the previous decade on the Masai giraffe populations in this study were important for the project style and interpretation of the outcomes; undergraduate student David Pearce; and college student Xiaoyi Hou, This work was supported by the Penn State Department of Biology, the Eberly College of Science, and the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences along with the Wild Nature Institute.