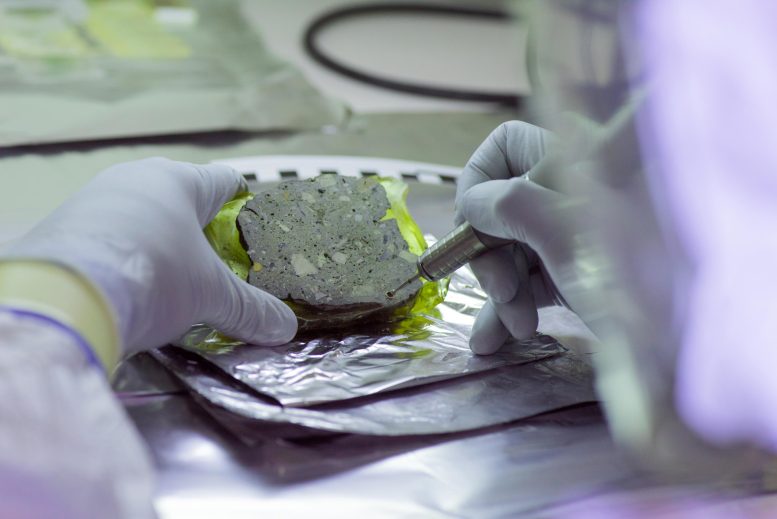

Surface of an area of undisturbed block of impregnated sediment from Denisova Cave. Credit: Mike Morley

The researchers successfully drawn out DNA from a collection of blocks of sediment prepared as long as 40 years earlier, from sites in Africa, Asia, Europe and North America. “The reality that these blocks are an outstanding source of ancient DNA– including that stemming from hominins– in spite of often decades of storage in plastic, supplies access to a vast untapped repository of genetic details. The research study opens up a new age of ancient DNA research studies that will review samples kept in laboratories, enabling analysis of websites that have long since been back-filled, which is specifically essential provided travel constraint and website inaccessibility in a pandemic world,” says Mike Morley from Flinders University in Australia who led a few of the geoarchaeological analyses.

Abundance of micro remains in the sediment matrix

The scientists utilized blocks of sediment from Denisova Cave, a site situated in the Altai Mountains in South Central Siberia where ancient DNA from Neanderthals, Denisovans and modern people has been obtained, and showed that little organic particles yielded more DNA than sediment sampled arbitrarily. “It plainly reveals that the high success rate of ancient mammalian DNA retrieval from Denisova Cave sediments comes from the abundance of micro remains in the sediment matrix rather than from totally free extracellular DNA from feces, physical fluids or decomposing cellular tissue possibly adsorbed onto mineral grains,” states Vera Aldeias, co-author of the research study and researcher at the University of Algarve in Portugal. “This study is a big step better to comprehend exactly where and under what conditions ancient DNA is preserved in sediments,” says Morley.

The method explained in the research study enables extremely localized micro-scale sampling of sediment for DNA analyses and shows that ancient DNA (aDNA) is not uniformly dispersed in the sediment; and that particular sediment features are more favorable to ancient DNA conservation than others. “Linking sediment aDNA to the historical micro-context implies that we can likewise deal with the possibility of physical motion of aDNA between sedimentary deposits,” says Susan Mentzer a scientist at the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment (Germany).

Diyendo Massilani, the lead author of the study, was able to recover significant amounts of Neanderthal DNA from only a few milligrams of sediment. He might identify the sex of the individuals who left their DNA behind, and revealed that they came from a population associated to a Neanderthal whose genome was previously reconstructed from a bone piece discovered in the cave. “The Neanderthal DNA in these little samples of plastic-embedded sediment was far more concentrated than what we generally discover in loose material,” he says. “With this approach it will become possible in the future to examine the DNA of many various ancient human people from simply a little cube of strengthened sediment. It is amusing to believe that this is probably so due to the fact that they utilized the cave as a toilet 10s of thousands of years back.”

Recommendation: “Microstratigraphic preservation of ancient faunal and hominin DNA in Pleistocene cavern sediments” 27 December 2021, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.DOI: 10.1073/ pnas.2113666118.

“The retrieval of ancient human and faunal DNA from sediments provides exciting new opportunities to examine the geographical and temporal distribution of ancient human beings and other organisms at sites where their skeletal remains are rare or absent,” states Matthias Meyer, senior author of the study and scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig.

To examine the origin of DNA in the sediment, Max Planck scientists teamed up with a global group of geoarchaeologists– archaeologists who use geological techniques to rebuild the development of sediment and sites– to study DNA preservation in sediment at a microscopic scale. The researchers utilized blocks of sediment from Denisova Cave, a website situated in the Altai Mountains in South Central Siberia where ancient DNA from Neanderthals, Denisovans and modern-day humans has actually been recovered, and showed that little organic particles yielded more DNA than sediment tested arbitrarily. “It clearly reveals that the high success rate of ancient mammalian DNA retrieval from Denisova Cave sediments comes from the abundance of micro remains in the sediment matrix rather than from complimentary extracellular DNA from feces, bodily fluids or decomposing cellular tissue potentially adsorbed onto mineral grains,” says Vera Aldeias, co-author of the research study and researcher at the University of Algarve in Portugal.

Tasting of an undisturbed block of impregnated sediment for ancient DNA analyses. Credit: MPI f. Evolutionary Anthropology

Ancient human and animal DNA can remain stably localized in sediments, protected in microscopic pieces of bone and feces.

Sediments in which archaeological finds are embedded have long been concerned by most archaeologists as unimportant by-products of excavations. In current years it has been shown that sediments can include ancient biomolecules, including DNA. “The retrieval of ancient human and faunal DNA from sediments uses interesting new chances to investigate the geographical and temporal distribution of ancient human beings and other organisms at sites where their skeletal remains are unusual or missing,” states Matthias Meyer, senior author of the study and researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig.

To examine the origin of DNA in the sediment, Max Planck researchers partnered with a global group of geoarchaeologists– archaeologists who use geological methods to rebuild the formation of sediment and sites– to study DNA conservation in sediment at a tiny scale. They used undisturbed blocks of sediment that had been previously gotten rid of from historical websites and taken in artificial plastic-like (polyester) resin. The hardened blocks were taken to the lab and sliced in areas for microscopic imaging and hereditary analysis.