8 Ways NYC Can Help Vulnerable Neighborhoods Survive Summertime Heat

With contributions by Robbie M. Parks, Jacqueline Klopp and Palak Srivastava

As severe heat ends up being an increasingly regular danger, it is critical the City of New York take bolder action to make sure frontline neighborhoods stay safe and cool throughout the summer season heat season. With the more frequent event of international crises like the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change-induced severe weather occasions, the City should prioritize attending to the cascading health threats these crises position for New York Citys most susceptible populations.

We belong to a group that just recently discovered that in the summertime of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and extreme heat combined to intensify health dangers for low-income communities of color. Our results have actually simply been published in the Journal of Extreme Events, and our team is made up of scientists from the Earth Institute at Columbia University and experts from the environmental justice group WE ACT. Listed below, we share a few of our findings and recommendations for how the City can much better safeguard vulnerable communities during the hot weather condition to come.

COVID, Inequality, and Extreme Heat: A Deadly Combination

Severe heat is the number one weather-related killer in the United States and New York City. The urban heat island result, where urban environments experience higher surface and air temperatures than rural and rural areas, intensifies the effects of extreme heat occasions and makes people in cities such as New York City particularly at high danger of unfavorable health outcomes. Beyond the metropolitan heat island impact, structural historical policies and social factors, such as racist redlining and zoning practices, have led to widespread disinvestment in facilities and contributed to raised temperature exposure in low-income neighborhoods of color.

by

Jenny Bock and Sonal Jessel|September 27, 2021

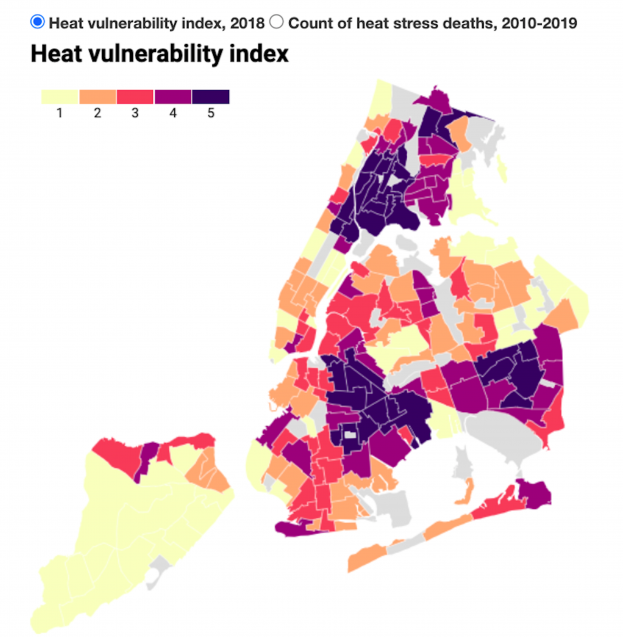

Severe heat positions lethal risks for low-income neighborhoods of color in New York City. In specific, Northern Manhattan and the South Bronx are two of the most heat-vulnerable areas in the city. Severe heat disproportionately impacts the citys Black neighborhoods, with Black New Yorkers accounting for 50% of heat-related deaths in NYC in between 2000 and 2012 even though they only make up 25% of the population. One of the most common factors that increase heat-related health threats for seniors and low-income people of color is their unequal access to cooling mechanisms, such as home a/c and good quality green areas that can alleviate the impacts of extreme heat.

The pandemic has also been especially deadly in low-income communities of color for similar factors. Comorbidities such as breathing diseases, high blood pressure, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, that make people more susceptible to passing away from extreme heat, are the exact same hidden health conditions that make people more vulnerable to dying from COVID-19. And environmental oppressions– such as disproportionate levels of air pollution, industrial advancement, and absence of access to green space– make low-income neighborhoods of color more likely to establish these underlying health conditions that increase their vulnerability to both COVID-19 and extreme heat.

COVID-19 offers a caution of what the future will look like when world issues and underlying social and economic conditions combine with the environment crisis, developing compound threats. Climate risks like extreme heat will just make crises like a worldwide pandemic that far more hazardous for susceptible neighborhoods.

Our Findings

Compounding dangers and crises need new kinds of readiness and catastrophe management by federal governments. The City of New York has actually carried out various government programs and policies to attend to the health impacts triggered by severe heat, including NYC Cool Roofs, Cool Neighborhoods NYC, Cool It NYC, the Be a Buddy program pilot, and by opening cooling centers and establishing a heat vulnerability index. New York State also administers a heating & cooling help program through the federally moneyed Low-Income Home Energy Assistance program (LIHEAP). Nevertheless, the heightened health threats brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic may have been what lastly pressed the City to make extreme heat a priority concern and buy the development of the Get Cool NYC program. Get Cool NYC is a free ac system program created during summertime 2020 that advocates had long requested to address the health impacts experienced by heat-vulnerable neighborhoods.

In an effort to better comprehend the intensifying health dangers triggered by COVID-19 and extreme heat, our group collected study reactions from WE ACT members to assess how individuals managed severe heat throughout the pandemic. Our study discovered that:

More people stayed indoors. Outcomes recommend individuals remained inside your home more due to COVID-19 and relied more on ac system (ACs) to remain cool.

Issues around visiting parks increased. People appeared to prevent green spaces due to concerns about overcrowding and distance to green areas from their homes.

There was unequal access to air conditioning. The outcomes point to a possible racial disparity in air conditioning gain access to, with air conditioner ownership and gain access to being highest among white respondents and lowest amongst Latinx and Black/African American participants.

To improve the usefulness of the Citys information tools, we suggest the City incorporate all the heat-related data it has into one publicly accessible, centralized area that shows mapping of heat vulnerability information, locations of hospitals, tree canopy cover and locations of green spaces and cooling features. We likewise advise that this central website share details about how individuals can take action to decrease their heat vulnerability and ought to link to more info about City and State cooling programs, such as the public cooling centers and the LIHEAP cooling help program.

In line with what community groups have actually asked for, the City must upgrade the heat-related death data it utilizes and broaden the indications it utilizes to determine heat-related death and heat vulnerability. The City must also reassess what variables it utilizes to create a heat index by considering other data sources for temperature level and the constructed environment, such as humidity and structure material type.

Increase neighborhood engagement and provide more chances for community input and feedback. Future research concerning heat vulnerability needs to bring in more targeted neighborhood feedback. For instance, the City can partner with neighborhood groups who are currently doing air quality monitoring to collect temperature level information using micro air quality screens. Community knowledge can assist the City determine where local temperature highs lie throughout areas. There should likewise be more regular surveying of neighborhoods to comprehend their needs and to assess how the Citys programs are performing in terms of fulfilling their requirements and keeping individuals safe throughout heat emergency situations.

Assess the efficiency of federal government environment resiliency policies and tools in targeting NYCs most heat-vulnerable communities. A comprehensive and organized evaluation of the Citys Heat Vulnerability Index tool and cooling programs is needed in order to determine how reliable they remain in decreasing heat vulnerability and targeting NYCs a lot of susceptible neighborhoods. We also recommend yearly methodical studies of the same areas be conducted to understand and examine the efficiency of cooling efforts over time.

Scale up heat mitigation and resiliency programs that develop neighborhoods brief- to long-lasting adaptive capability to react to extreme heat. Supporters have long been asking the City and State to provide more interventions and funding to support community readiness and address a/c gain access to and facilities issues that add to higher heat vulnerability for low-income communities of color. The City can direct funds from sources such as the American Jobs Plan, the upcoming federal infrastructure strategy for building upgrades including weatherization, revenue produced from Local Law 97s emission costs, and the 2022 NYC budget plan, that includes significant financing for scaling up energy performance and solar on city-owned buildings.

Expand eligibility requirements for the LIHEAP program to finance sustainable cooling installation and energy effectiveness retrofits for low-income renters and house owners. Community groups along with federal government authorities suggest NY State reform the LIHEAP program to make it simpler for vulnerable populations to sign up for the program, and to broaden it to supply summer season energy bill support, as the State did temporarily during the COVID-19 pandemic, utilizing the increased federal financing for the program.

Plant vegetation and broaden green areas in areas with high heat vulnerability to reduce the city heat island effect and offer neighborhoods with a safe space to cool down, and offer other extra long-term health advantages.

Use legal mechanisms to prioritize securing heat-vulnerable neighborhoods. Policies such as the proposed City Council costs 1563-2019– which codifies the Citys cooling center program– and the recently enacted City Council law 1960-2020, which requires the City to send a heat strategy each year, need to be executed with a core equity focus in order to designate long-term resources and institutionalise these crucial, life-saving programs.

These findings have actually highlighted a couple of essential points. Initially, the COVID-19 pandemic increased the need to speed up efforts to improve targeted interventions like the Citys totally free air conditioning and cooling center programs, HVAC retrofitting through LIHEAP, and green space growth to highly heat-vulnerable areas. Second, there is a need to develop more powerful environmental justice neighborhood networks and feedback systems to sign in on affected residents. Additionally, our research study partnership highlights the importance of consulting and engaging with environmental justice neighborhoods and companies like WE ACT that have put forth data-driven and community-informed policy suggestions for how the City and State can reform their heat resiliency programs to make them more fair and simply.

How the City and State Can Better Protect Heat-vulnerable New Yorkers

The study results, while exploratory and initial, reinforce the previously observed pattern that there is a racial disparity in access to and use of cooling mechanisms such as air conditioning and green area. The study results likewise align with the issues revealed by neighborhood groups and city officials around the urgent requirement to provide personal indoor cooling to vulnerable populations due to social distancing measures.

The metropolitan heat island impact, where metropolitan environments experience higher surface and air temperatures than suburban and rural areas, intensifies the effects of severe heat occasions and makes people in cities such as New York City especially at high threat of adverse health results. The City of New York has implemented numerous federal government programs and policies to resolve the health effects triggered by extreme heat, consisting of NYC Cool Roofs, Cool Neighborhoods NYC, Cool It NYC, the Be a Buddy program pilot, and by opening cooling centers and developing a heat vulnerability index. To improve the usefulness of the Citys data tools, we suggest the City integrate all the heat-related information it has into one publicly accessible, centralized area that shows mapping of heat vulnerability information, locations of healthcare facilities, tree canopy cover and locations of green spaces and cooling facilities. A extensive and organized evaluation of the Citys Heat Vulnerability Index tool and cooling programs is required in order to determine how reliable they are in lowering heat vulnerability and targeting NYCs a lot of susceptible neighborhoods. Scale up heat mitigation and resiliency programs that build communities brief- to long-lasting adaptive capability to react to extreme heat.

With existing financing streams going out for interventions such as the Citys tree planting effort and Be a Buddy programs, the future of these health equity-focused programs is uncertain. With more regular worldwide crises and severe weather occasions only heightening health dangers for susceptible populations, the requirement for these types of interventions will be even higher in the future

.

This study was funded by the Columbia University Earth Frontiers-funded job Climate strength in Northern Manhattan and the South Bronx: Collaborative, community-led policy research study about heat vulnerability in New York City. Jenny Bock is a recent graduate of Columbia Universitys MPA in Environmental Science and Policy program. Sonal Jessel is director of policy at WE ACT for Environmental Justice. The research studys authors likewise included Robbie M. Parks, Earth Institute post-doctoral research study fellow and senior author of the research study; Jacqueline Klopp, research study scholar and co-director of the Center for Sustainable Urban Development, and Palak Srivastava, Stuyvesant High School senior.