New Environment Migration Modelling Puts a Human Face on Environment Impacts

The Climate Schools Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) has as soon as again partnered with the Bank, the CUNY Institute for Demographic Research, and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impacts Research to model the staying World Bank Regions. The predicted total of “climate migrants” by 2050 in the countries included in Map 1 is between 48 million (at the low end of the environment friendly circumstance) and 216 million (at the high end of the downhearted situation).

While the likely geographical circulation and numbers of migrants are practically certain to be different by 2050 than what we forecast, the report and modeling work has actually successfully created space for discussion with policy makers about the actions required to prepare for most likely boosts in migration and displacement owing to environment impacts. (I address elsewhere that the term “environment migrants” is imprecise, and that they are best conceived of as distressed or mixed migrants who move at least in part owing to environment impacts.).

The reality is that the transboundary climate-induced migration that will happen is more likely to be between nations in the worldwide South, who already disproportionately bear the force of the environment impacts resulting from the Norths fossil-fueled advancement since the dawn of the commercial transformation.

Building the resilience of communities in climate-impacted areas so they can adjust locally instead of need to move. These include measures such as catastrophe danger reduction (DRR) and climate-adaptive agriculture. But governance measures are also critical, considering that findings indicate that corruption and suspect in organizations is a motivator for worldwide migration.

Assisting in movement by assisting those who want or require to migrate, to both fund the migration and much better insert themselves in location locations. This might include money transfers to cover travel costs or to assist in mobility in between nations after catastrophes, or efforts to set up migration passages for pastoralists. These programs are just getting going, and face some resistance provided the traditional inactive predisposition in the majority of development programming.

Planned relocation (or resettlement) is being utilized in a minimal number of cases around the establishing world with some success, though the expenses are generally high, and the process is stuffed. Short-distance relocations far from the coast, for example, are more most likely to be effective than longer range relocation. In some circumstances house buyouts might be more effective, leaving the choice as to where to relocate as much as the families.

Supporting destination areas, e.g., through concessional financing to countries that get large numbers of refugee/ displaced people from natural disasters (an effort by the World Bank), or dealing with displaced neighborhoods straight to develop their DRR preparation and reaction capacity (an effort by IOM).

New climate migration modeling work jobs increased numbers of individuals moving within their countries in the establishing world– as many as 216 million internal migrants by 2050. The modeling completes work for the World Bank that was released in 2018 as volume 1 of Groundswell. The Climate Schools Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) has once again partnered with the Bank, the CUNY Institute for Demographic Research, and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impacts Research to model the remaining World Bank Regions. The completed work, now launched in Groundswell Part II, focuses on three new areas– North Africa, Central America, and the Lower Mekong– and consists of evaluations of climate migration concerns for small island establishing states (SIDS) and the Middle East. The projected total of “environment migrants” by 2050 in the countries included in Map 1 is between 48 million (at the low end of the climate friendly scenario) and 216 million (at the high-end of the pessimistic circumstance).

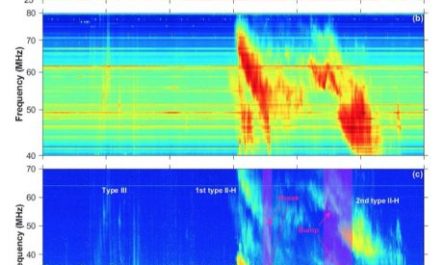

Map 1. Areas modeled.

In doing so, it puts a “human face” on climate effects. While the most likely geographic circulation and numbers of migrants are nearly particular to be various by 2050 than what we predict, the report and modeling work has actually successfully created area for dialogue with policy makers about the steps required to prepare for likely increases in migration and displacement owing to climate effects. (I attend to in other places that the term “climate migrants” is inaccurate, and that they are best conceived of as blended or distressed migrants who move at least in part owing to environment effects.).

Map 2. Hotspots of in- and out-migration for North Africa, 2050.

At the time of the 2018 release, I published a post on the need to prepare for climate migration and the policy alternatives for doing so. In the interim, Ive begun exploring in higher depth the methods which advancement firms are dealing with environment movement, and ways to improve this practice. A few of this thinking is revealed in an open access short article in Population & & Environment that I just recently published with associates in Europe and the US. In that post we examine advancement agency task documents and reports to assess what techniques are being required to attend to climate mobility, and what we ought to do. Techniques that are currently being taken can be broken down into 3 classifications:.

Additional policy guidance in response to the Biden administrations executive order on climate migration is offered from this Refugees International Task Force report, on which I had the opportunity to serve. The task force came up with two packages of steps– one created to lessen the need to move and another to offer defense for displaced persons and migrants– that show much of the same methods pointed out above.

In a more forward looking vein, my co-authors and I advise three types of action. One is to move beyond the investigation of physical climate impacts to look at social feedbacks, or what is in some cases termed social tipping points, that might increase or reduce the tendency to move. This will need a better understanding of how development and adaptation interventions may be assisting or injuring communities that desire to remain in place. Another is to support metropolitan centers as getting areas of climate-induced migration and displacement, and to upgrade slums and squatter settlements that are often the top place of arrival. Lastly, it will be essential to utilize global migrant ties for advancement, consisting of promoting the role of remittances in supporting strength and those who stay behind.

The truth is that the transboundary climate-induced migration that will occur is more likely to be between countries in the global South, who already disproportionately bear the impact of the climate impacts resulting from the Norths fossil-fueled development given that the dawn of the industrial revolution. We owe it to those countries and to the migrants to commit more development support to attending to the needs of those displaced by environment change.

Alex de Sherbinin is an associate director and a senior research study researcher at CIESIN, and a lead author on the Groundswell report series.