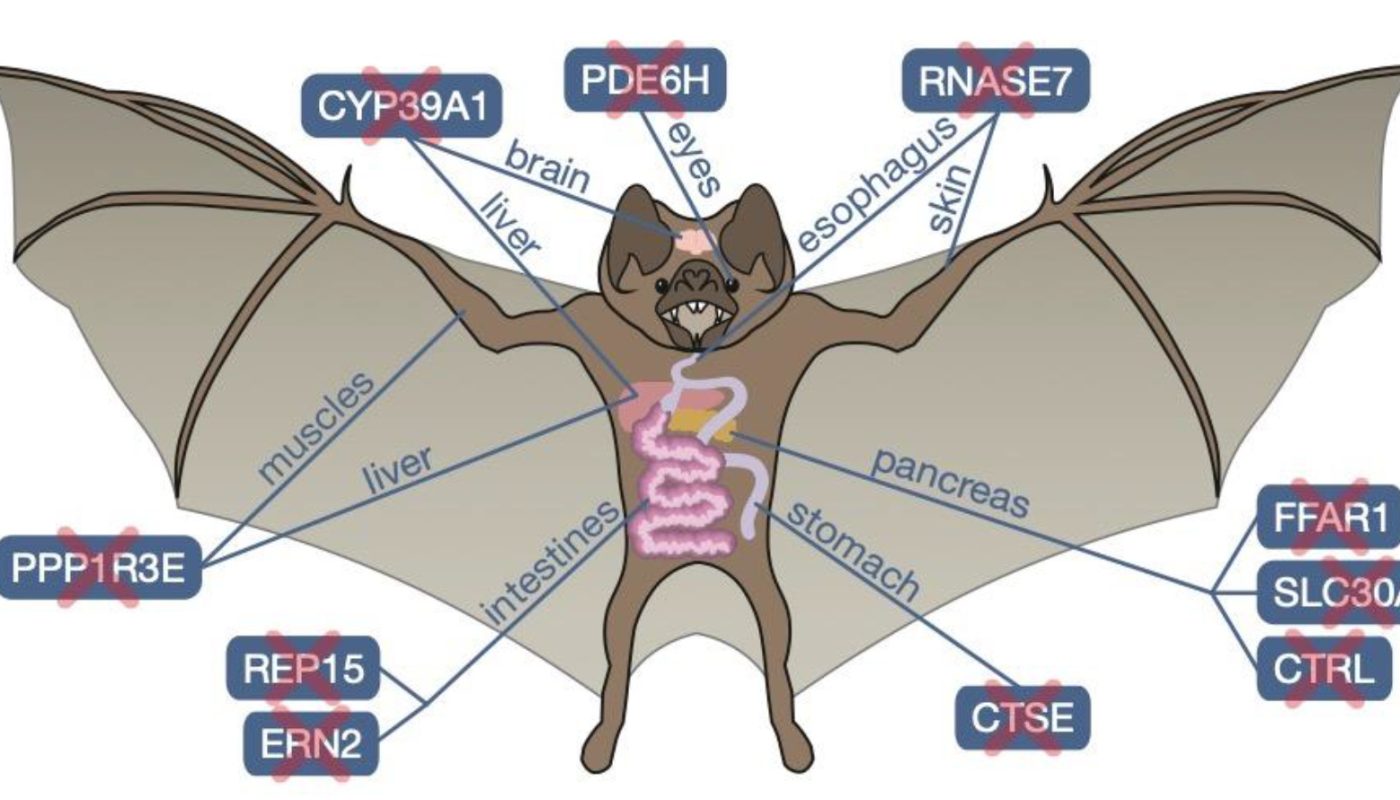

Vampire bats have a lavish diet. As their name recommends, they feed specifically on blood from other animals that they hunt in the dark. Getting all of their nutrients from this gory source is challenging, though. Blood is rich in protein, but especially light on fat and sugars. Previous research studies, including an earlier recommendation genome, have actually looked for to understand how vampire bats adjusted to live off this strange diet plan, however an analysis of a new, much more complete and precise genome sequence for the species, uploaded as a preprint to bioRxiv October 19, lends brand-new insights into this question. Comparing the newly put together, reference-quality genome of the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus)– one of the 3 extant vampire bat types– to 25 genomes for other type of bats revealed 13 genes that were missing out on specifically in this types. These losses might have contributed to the vampire bats preference and capability to dine on blood and to other characteristics, such as their remarkable cognitive aptitudes. Even amongst bats, vampire bats are considered smart, social animals; theyre known to regurgitate blood to roostmates dealing with hunger, specifically to those who shared blood with them in the past.The types first genome– sequenced together with the animals gut metagenome– revealed some genomic signatures related to sanguivory, and highlighted the role of gut microbes in supplying nutrients not readily offered in blood. While that research study “gave us a lot of details” University of California, Berkeley, bioinformatician Yocelyn Gutiérrez-Guerrero (who was not included in either genomic analysis) informs The Scientist in Spanish, the new genomes greater resolution and sequencing depth, enabled by enhanced sequencing technologies, provides “more detail of the genomic landscape” and greater insight into the bats adaptations for blood feeding. The new analysis, which has actually not yet undergone peer review, compared D. rotundus with 25 bat species, 16 more than were readily available at the time of the previous genome sequence. In specific, the brand-new research study consisted of 6 just recently sequenced species from the vampire bats family, the leaf-nosed bats (Phyllostomidae). The inclusion of these relatives, especially some of the types closest sis family trees, “allows us to pinpoint just what occurred on this branch … resulting in the vampire bats,” states Michael Hiller, a genomicist at the LOEWE Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics in Germany and coauthor of the preprint. Losing a gene implies not having a practical copy of it any longer. This might occur by having it totally erased from the genome or by having remnants of it for which the reading frame is “ruined so much with frameshifts, early stop codons, and other mutations” that the gene is not likely to code for a practical protein, states Hiller.Developing techniques to identify gene losses is challenging. Sequencing errors, alignment issues, or evolutionary changes that customize genes but do not inactivate them could result in misidentifying whether a gene is practical. Early studies on gene losses included a great deal of manual curation. Recently, Hiller and his group have been working on precisely finding gene losses on a bigger scale in mammalian types, exposing the role of this genomic change in different phenotypic adaptations. Hiller discusses that now, his group desired to examine “whether the loss of ancestral genes might have contributed [to the] physiological and metabolic changes” connected with the “very unique diet plan” of the vampire bat.Gene losses frequently follow dietary specializations “when some genes are not required in an [animals] life” anymore, composes Huabin Zhao, a molecular evolutionary biologist at Wuhan University in China who did not take part in the new study, in an e-mail to The Scientist. Prior to the sequencing of the first vampire bat genome, Zhao and his coworkers had actually identified losses of taste receptor genes for bitter and sweet flavors in the bats, which represent 3 of the 13 losses noted in the preprint.An illustration of organs and anatomical websites where the 10 recently discovered missing genes play crucial rolesThe staying 10 had actually not been previously reported, according to the authors. A lot of them offer tips as to how the bats get the most nutrition from blood, which is infamously nutrient poor, states Gutiérrez-Guerrero. Amongst the genes lost by D. rotundus are 2 likely associated with boosting insulin secretion. The bats may not need much insulin provided the low amount of sugar in their diet. In reality, it was formerly revealed that they dont secrete much insulin, states Hiller, which might come from a need to keep the limited glucose gotten from their diet readily available in their blood stream. The bats also lack a gene believed to be involved in inhibiting trypsin, an enzyme which participates in protein digestion and absorption. Greater levels of trypsin activity might ultimately help them digest their protein-rich diet plan. On the other hand, the loss of the REP15 gene might be enhancing iron excretion, keeping the bats from becoming poisoned by the metal, which is plentiful in blood. Some of the newly determined gene losses talk to other elements of the animals way of life, the authors recommend. One of them appears to be connected to vampire bats social capabilities: they do not have a gene that deteriorates 24S-hydroxycholesterol, a cholesterol metabolite known to play numerous roles in brain development and functioning. This loss might imply the bats have higher levels of the metabolite in their brains, something revealed to improve spatial memory in mice, and which may account for the bats exceptional social memory. See “Social Bonds Among Captive Vampire Bats Persist in the Wild” Even though D. rotundus is an iconic types that has actually been well studied at the physiological and morphological level, caveats and unpredictabilities about the practical effects of the gene losses remain, because “we still have many gaps in our understanding,” says Hiller. For example, the new analysis suggested that the antimicrobial gene RNASE7 is functionally absent in the vampires, while the previous genomic analysis recommended it was under positive selection– the mutations found were interpreted as increasing its bactericidal capacity. The contrasting findings spur more questions. Zhao recommends this could indicate that the suspending mutations detected by Hillers team are not present in all people of the types; Hiller states this would be “extremely unlikely” offered the variety of anomalies present in RNASE7. If RNASE7 is indeed nonfunctional in D. rotundus, future research studies will need to recognize precisely what pathogens are targeted by its protein and what it does in other bat species.Hiller says he and his group would likewise like to look at choice, gene duplications, the expansion of gene households, and differences in gene expression in the future, to obtain “a more total photo of the genomic modifications that are involved in blood feeding.” Furthermore, Hiller says that he and his colleagues are dealing with genome assemblies for the other two types of vampire bat to see whether they share gene losses with D. rotundus..

Comparing the newly assembled, reference-quality genome of the typical vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus)– one of the 3 extant vampire bat species– to 25 genomes for other kinds of bats revealed 13 genes that were missing out on exclusively in this species. Even among bats, vampire bats are considered clever, social animals; theyre understood to spit up blood to roostmates facing starvation, particularly to those who shared blood with them in the past.The types first genome– sequenced together with the animals gut metagenome– revealed some genomic signatures associated with sanguivory, and highlighted the function of gut microbes in supplying nutrients not readily available in blood. In specific, the brand-new research study included six just recently sequenced species from the vampire bats family, the leaf-nosed bats (Phyllostomidae). Prior to the sequencing of the very first vampire bat genome, Zhao and his colleagues had recognized losses of taste receptor genes for sweet and bitter tastes in the bats, which account for 3 of the 13 losses kept in mind in the preprint.An illustration of organs and anatomical websites where the 10 newly found missing genes play important rolesThe remaining 10 had not been formerly reported, according to the authors. One of them appears to be linked to vampire bats social capabilities: they lack a gene that degrades 24S-hydroxycholesterol, a cholesterol metabolite understood to play various functions in brain advancement and functioning.