When considered to be uniquely for the advantage of terrestrial plants, the matchmaking abilities of insects, birds, and bats were discovered to be shared by marine animals a few years back, when researchers reported that nighttime invertebrates pollinate the flowers of a seagrass types. A research study released online today (July 28) in Science shatters yet another pollination paradigm by showing that a small shellfish types assists in the fertilization of the red alga Gracilaria gracilis. Thus, the nonmotile spermatia “have to discover their way to the female plant,” she explains, and up until now it was believed that they did so by relying exclusively on abiotic aspects such as water currents.But while collecting the algae for study, Valero and her associates always found little crustaceans of one to a few centimeters long around it, she recounts. The animals discover shelter in the algae and food in the kind of diatoms. The distinction was striking: the aquarium including shellfishes had an average of about 20 times more cystocarps per centimeter of female body than the control.Then, to check whether the increased fertilization in the presence of the animals could be due to the flow of water created by their motion, or whether they directly bring spermatia, Valero and her associates performed a second experiment.

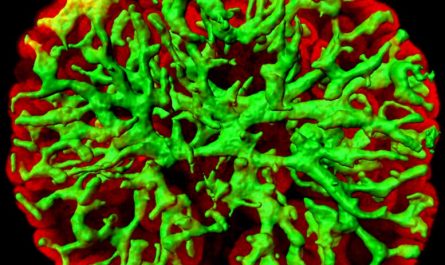

When thought about to be uniquely for the advantage of terrestrial plants, the matchmaking capabilities of bugs, birds, and bats were found to be shared by marine animals a couple of years earlier, when researchers reported that nighttime invertebrates pollinate the flowers of a seagrass types. A study published online today (July 28) in Science shatters yet another pollination paradigm by showing that a little crustacean types helps with the fertilization of the red alga Gracilaria gracilis. This is the first evidence of animal-mediated “pollination” in a photosynthetic organism coming from a group that is far more ancient than land plants. The leader of the research study, Myriam Valero, a population geneticist at Roscoff Marine Station in France, describes that the reproductive cycle of red algae shares some resemblances with that of land plants. The male gametes– called spermatia– are not flagellated, and the female gametes are not released into the water. Thus, the nonmotile spermatia “have to find their method to the female plant,” she explains, and previously it was thought that they did so by relying entirely on abiotic aspects such as water currents.But while gathering the algae for research study, Valero and her associates always found little crustaceans of one to a few centimeters long around it, she recounts. At first glance, these animals (Idotea balthica) are challenging to see in the field, she says, because they share the algaes color “and they are rather mimetic.” But as soon as you bring the seaweed into the lab, you can see numerous them. The animals find shelter in the algae and food in the form of diatoms. The scientists started to question whether the constant existence of these creatures might be helping to move the algaes male gametes to the female organ. They initially evaluated their hypothesis by positioning male and female G. gracilis individuals 15 centimeters apart in fish tank with calm seawater, lessening the possibility that water movement could intervene in fertilization. In one set of aquaria, they added I. balthica, and in the other they did not. After one hour, they measured the number of fertilized zygotes, called cystocarps, which are visible to the naked eye. The difference stood out: the fish tank including shellfishes had an average of about 20 times more cystocarps per centimeter of female body than the control.Then, to test whether the increased fertilization in the existence of the animals could be due to the flow of water created by their motion, or whether they directly carry spermatia, Valero and her colleagues carried out a 2nd experiment. They preincubated the shellfishes with male seaweed in its sexual phase for one hour, then moved them to an aquarium consisting of just G. gracilis females. The fertilization success after one hour in the presence of I. balthica was again significantly higher than in a control aquarium without them. Young shellfish (Idotea balthica) carrying stained spermatia of Gracilaria gracilis on its body. Three-dimensional restoration from confocal laser scanning microscopy.Sebastien Colin; Max Planck Institute for Biology, Tubingen, Germany; Station Biologique de Roscoff, CNRS, SU, Roscoff, FranceValero acknowledges, nevertheless, that they did not test for the relative value of animal transportation versus that of water flow, and hypothesizes that in the wild this might depend upon ecological conditions. For example, the shellfishes help may be more appropriate when the algae experience low tides and the water is relatively calm, she says.”We actually have no idea” about how important animal-mediated marine pollination is, concurs Brigitta van Tussenbroek, an ecologist at the Institute of Marine Sciences and Limnology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico whose team first explained underwater pollination of a seagrass types. Both researchers concur that this is a crucial question yet to be answered. Van Tussenbroek, who was not included in the new study, includes that its “truly fantastic” that the authors have actually discovered proof of animal pollinators in another aquatic photosynthetic organism “totally unassociated in evolutionary terms … to seagrasses.” Algae and seagrass may not be evolutionarily associated, however they remain in the very same setting and share “the exact same ecological pressures,” she notes. It was just a matter of time before another circumstances of underwater pollination by animals was discovered, she states, including that this phenomenon is most likely “not unique to these two.” Like this article? You might also enjoy our quarterly life newsletter, which is filled with stories like it. You can sign up for free here.