A brand-new theory suggests the utility of a memory for future circumstances dictates its area in the brain, either in the hippocampus or the neocortex. This challenges the classical view by emphasizing that memories combine to the neocortex based upon their generalizability, not age.

According to a brand-new theory presented by researchers at HHMIs Janelia Research Campus and their coworkers at University College London, how helpful a memory is for future scenarios figures out where it resides in the brain.

The theory provides a new way of understanding systems consolidation, a procedure that moves particular memories from the hippocampus– where they are initially kept– to the neocortex– where they live long term.

Under the classical view of systems combination, all memories move from the hippocampus to the neocortex over time. This view does not always hold up; research study reveals some memories permanently reside in the hippocampus and are never ever moved to the neocortex.

Over the last few years, psychologists proposed theories to discuss this more complicated view of systems combination, but nobody has yet found out mathematically what identifies whether a memory remains in the hippocampus or whether it is combined in the neocortex.

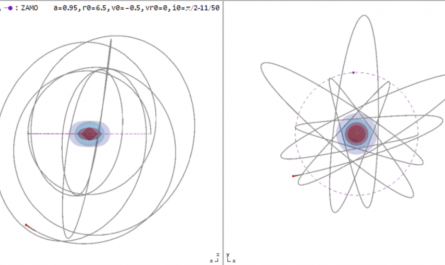

Now, Janelia researchers are putting forward a brand-new, quantitative view of systems consolidation to assist resolve this longstanding issue, proposing a mathematical neural network theory in which memories consolidate to the neocortex just if they improve generalization.

Generalizations are constructed from the predictable and trustworthy elements of memories, enabling us to apply them to other situations. We can generalize specific functions of memories to help us comprehend the world, like the truth that canyons anticipate the presence of water.

This is various from episodic memories– detailed recollections of the past that have distinct functions like an individual memory we have of treking to a particular canyon and coming upon a body of water.

Under this view, consolidation does not copy memories from one location of the brain to another but rather produces a brand-new memory that is a generalization of previous memories. The quantity that a memory can be generalized– not its age– figures out whether it is combined or remains in the hippocampus.

The scientists utilized neural networks to show how the quantity of debt consolidation varies based upon how much of a memory is generalizable. They had the ability to recreate previous speculative patterns that could not be described by the classical view of systems consolidation.

The next action is to check the theory with experiments to see if it can predict just how much a memory will be consolidated. Another important instructions will be to evaluate the authors models of how the brain may differentiate in between unforeseeable and predictable components of memories to control consolidation. Revealing how memory works can assist scientists better comprehend an integral part of cognition, potentially benefitting human health and expert system.

Reference: “Organizing memories for generalization in complementary knowing systems” by Weinan Sun, Madhu Advani, Nelson Spruston, Andrew Saxe and James E. Fitzgerald, 20 July 2023, Nature Neuroscience.DOI: 10.1038/ s41593-023-01382-9.

The next action is to test the theory with experiments to see if it can anticipate how much a memory will be combined. Another important instructions will be to evaluate the authors models of how the brain may distinguish in between foreseeable and unforeseeable components of memories to manage combination. Revealing how memory works can help researchers much better understand an integral part of cognition, potentially benefitting human health and artificial intelligence.