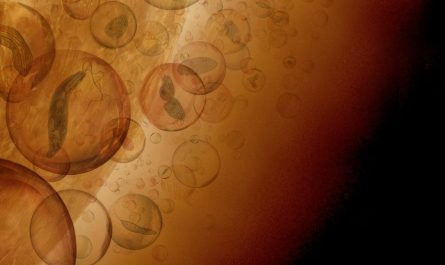

A mosquito caught in amber is the earliest fossil of its kind. Credit: Existing Biology.

The oldest fossil mosquito, caught in Lebanese amber from the Lower Cretaceous duration, challenges the current understanding of mosquito development.

The unspoiled fossil, Libanoculex intermedius, suggests a potential early blood-feeding behavior in both male and female mosquitoes.

This ancient mosquito, 30 million years older than previous fossils, suggests male mosquitoes may have eaten blood, unlike today.

In a striking discovery, scientists have uncovered the oldest-known mosquito fossil in amber from Lebanons Lower Cretaceous period. The pristinely preserved fossil exposes two male mosquitoes geared up with piercing mouthparts, recommending ancient males eaten blood, unlike their modern-day equivalents. Presently, just female mosquitoes suck blood. This discovery not only presses back the timeline of mosquito evolution however also challenges pre-existing beliefs about their feeding routines.

Challenging blood-feeding presumptions

” Lebanese amber is, to date, the oldest amber with intensive biological additions, and it is a very important material as its development is synchronous with the look and beginning of radiation of blooming plants, with all that follows of co-evolution between pollinators and flowering plants,” says Dany Azar of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Lebanese University.

The researchers note that the Culicidae household, to which mosquitoes belong, is believed to have come from in the Jurassic duration (200 to 145 million years ago) based on previous studies of mosquito genomes. This amber fossil– now the earliest mosquito fossil to date– is dated to the early Cretaceous.

Libanoculex intermedius. Credit: Current Biology.

The fossilized mosquito, framed in amber, uses a window into the Cretaceous period, a time marked by significant shifts in the development of life and the increase of angiosperms (flowering plants) about 130 million years ago.

The evolution of mosquito blood-feeding

This discovery clarifies the “ghost-lineage gap” in the mosquito fossil record. It recommends that blood-feeding behavior might have been present in both sexes in ancient times, just to be lost in males later in their evolutionary history. This raises intriguing questions about the evolutionary and eco-friendly pressures that may have caused such a substantial behavioral shift.

The brand-new fossil, recognized as Libanoculex intermedius, informs a various story. This ancient male mosquito displays strong, sharp, and denticulate (tooth-like) mouthparts meant to pierce through skin. Such a finding suggests that ancient male mosquitoes might have been blood feeders (hematophagous).

The existence of particular types of sensilla (sensory organs) on the pests mouthparts recommends a sensory adjustment that might have assisted in identifying hosts or mates, further supporting the hypothesis of hematophagy.

In a striking discovery, scientists have uncovered the oldest-known mosquito fossil in amber from Lebanons Lower Cretaceous duration. The pristinely preserved fossil exposes 2 male mosquitoes equipped with piercing mouthparts, recommending ancient males fed on blood, unlike their modern-day counterparts. The scientists keep in mind that the Culicidae household, to which mosquitoes belong, is believed to have actually originated in the Jurassic duration (200 to 145 million years ago) based on previous research studies of mosquito genomes. Typically, female mosquitoes are understood for their blood-feeding behavior, a characteristic that has made them infamous as vectors for various diseases. Such a finding implies that ancient male mosquitoes may have been blood feeders (hematophagous).

What truly sets this discovery apart is the nature of the fossilized mosquito itself. Normally, female mosquitoes are known for their blood-feeding habits, a quality that has made them notorious as vectors for various illness. Males, on the other hand, are typically nectar feeders.

The findings appeared in the journal Current Biology.