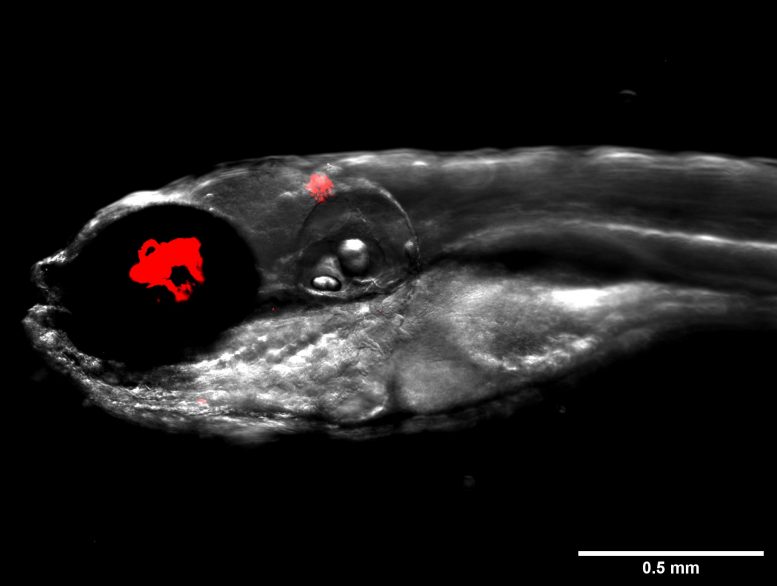

Zebrafish contaminated with fluorescent germs, Mycobacterium abscessus, revealed in red. Credit: Dr. Matt Johansen and the Kremer Lab

Mycobacterium abscessus, a relative of the bacteria that cause tuberculosis and leprosy, is accountable for especially extreme damage to human lungs and can be resistant to many basic antibiotics, making infections very challenging to deal with. Nevertheless, there is hope. Bacteria are susceptible to naturally taking place viruses, called bacteriophages; for each types of bacteria, there is an unique bacteriophage that will damage it. Researchers are evaluating brand-new therapies that combine bacteriophages with the antibiotics that we currently use, to deal with antibiotic-resistant infections. In their present Disease Models & & Mechanisms article, Laurent Kremer and associates from Université de Montpellier, France, and University of Pittsburgh, USA, examine the anti-bacterial effects of a new mix therapy, treating infections brought on by the antibiotic-resistant germs M. abscessus with a bacteriophage and an antibiotic.

Formerly, the Pittsburgh group had actually recognized one bacteriophage out of 10,000, called Muddy, that effectively eliminates germs in a petri dish and might be a candidate for dealing with these infections in people. However, the group wanted to discover an alternative to testing their new treatment in clients. Knowing that human cystic fibrosis patients are particularly susceptible to M. abscessus infections, Kremer and colleagues decided to test their brand-new combination treatment on zebrafish carrying the essential hereditary mutation that triggers cystic fibrosis in mimics and humans how our body immune system reacts to bacterial infections. The team obtained samples of an antibiotic-resistant kind of M. abscessus from a cystic fibrosis patient to contaminate the cystic fibrosis zebrafish and check their brand-new treatment.

Keeping an eye on the animals for 12 days, they found that the fish established severe infections with abscesses and suffered a high death rate; only 20% made it through. This time, the fish had much less severe infections, increased opportunities of survival (40%) and had less of the abscesses suffered by the fish throughout a severe infection.

Then the authors looked for an antibiotic to combine up with Muddy and found that rifabutin could deal with the M. abscessus infection as efficiently as the bacteriophage alone. After recognizing rifabutin, Kremer and associates dealt with the infected fish for 5 days with the antibiotic and bacteriophage. With this combination treatment, the fishes infections were much less severe; the fishes survival rate soared to 70% and they suffered far less abscesses. This is a dramatic improvement compared to fish treated with only the antibiotic, which had a 40% survival rate.

Having actually shown that it is possible to treat an antibiotic-resistant infection in vulnerable zebrafish with specifically targeted bacteriophages, the authors hope this treatment can eventually be moved to the center to start saving human lives. Matt Johansen (Université de Montpellier, France) is positive that zebrafish will continue to play an essential role in our battle versus antibiotic-resistance, saying “We believe that zebrafish will assist us understand lots of bacteriophage-bacteria pairings in our fight versus multi-drug resistant pathogens.”

Referral: “Mycobacteriophage– antibiotic treatment promotes enhanced clearance of drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus” 16 September 2021, Disease Models & & Mechanisms.DOI: 10.1242/ dmm.049159.

Mycobacterium abscessus, a relative of the germs that trigger tuberculosis and leprosy, is responsible for especially severe damage to human lungs and can be resistant to many standard prescription antibiotics, making infections exceptionally challenging to deal with. Scientists are checking new treatments that integrate bacteriophages with the prescription antibiotics that we currently utilize, to treat antibiotic-resistant infections. Previously, the Pittsburgh group had determined one bacteriophage out of 10,000, understood as Muddy, that efficiently kills bacteria in a petri dish and might be a prospect for treating these infections in people. Having revealed that it is possible to deal with an antibiotic-resistant infection in susceptible zebrafish with specifically targeted bacteriophages, the authors hope this treatment can eventually be moved to the clinic to begin saving human lives.