Why the U.S. Northeast Coast Is a Worldwide Warming Location

Heat Linked to Rising Ocean Temperatures, Altered Wind Patterns

From Maine to Delaware, the seaside U.S. Northeast is warming faster than a lot of regions of North America, and a brand-new research study shows why. It connects the outsize heating to unusually fast-rising temperatures in the North Atlantic Ocean, and alterations in wind patterns that are now tending to send out the heat to the U.S. coast instead of the other method. The research appears today in the journal Nature Climate Change.

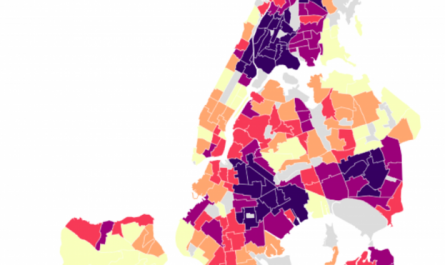

As a result of the modifications, not only are Northeastern winter seasons getting warmer, as long projected by climate designs, however rapid and substantial summer warming is happening also. “Some of the greatest populations centers in the U.S. are suffering the best degree of warming,” stated lead author Ambarish Karmalkar, a teacher of geosciences at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. “This warming is being driven both by similarly rapid trends in the Atlantic Ocean and by modifications in climatic circulation patterns.”

Increasing Atlantic Ocean temperature levels and altered wind patterns that blow the heat toward land are helping heat the U.S. Northeast coast at a quick speed. Here, lower Manhattan under a summertime sky. (Kevin Krajick/Earth Institute).

Beyond that, a number of recent studies indicate that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a system of long-distance Atlantic currents, is slowing down due to climate change. As climate warms, and glaciers in Greenland melt and send fresh water into the ocean, the conveyor is stalling. One effect is even more heating of the ocean off the Northeast coast.

One link in between the AMOC and increasing temperatures along the coast is the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), a cyclic weather phenomenon that governs the strength and position of the winds that blow from the United States over the Atlantic and on to Europe. The study shows that the NAO has for the previous few decades tended to settle into a pattern that boosts the flow of ocean air towards the eastern coast.

While scientists already learn about the unusual rate of warming in the region, computer designs, which attempt to imitate the forces at work, have up until now failed to reproduce the pattern. Radley Horton, a climate scientist at Columbia Universitys Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and coauthor of the new research study, states the rising Atlantic temperatures and modified wind patterns are the missing out on links.

” Climate models stay our finest tool for projecting future environment risks in the populous and exposed seaside Northeast U.S.,” he said. “But the inability of those models to reproduce the observed summer season pattern of improved seaside land warming relative to inland regions points to a possible blind spot.”.

The research shows that researchers should utilize a new generation of high-resolution climate models that might more properly record modifications in local environment, say the authors. “Our research study indicates that without enhanced high resolution information, regional climate assessments, which inform out capability to prepare for the future, might under-emphasize warming in this populated region,” said Karmalkar.

It connects the outsize heating to abnormally fast-rising temperature levels in the North Atlantic Ocean, and modifications in wind patterns that are now tending to send the heat to the U.S. coast instead of the other way. “This warming is being driven both by equally fast patterns in the Atlantic Ocean and by modifications in climatic circulation patterns.”

Increasing Atlantic Ocean temperature levels and altered wind patterns that blow the heat towards land are helping heat the U.S. Northeast coast at a fast pace. Beyond that, several current studies indicate that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a system of long-distance Atlantic currents, is slowing down due to environment change. As climate warms, and glaciers in Greenland melt and send fresh water into the ocean, the conveyor is stalling.