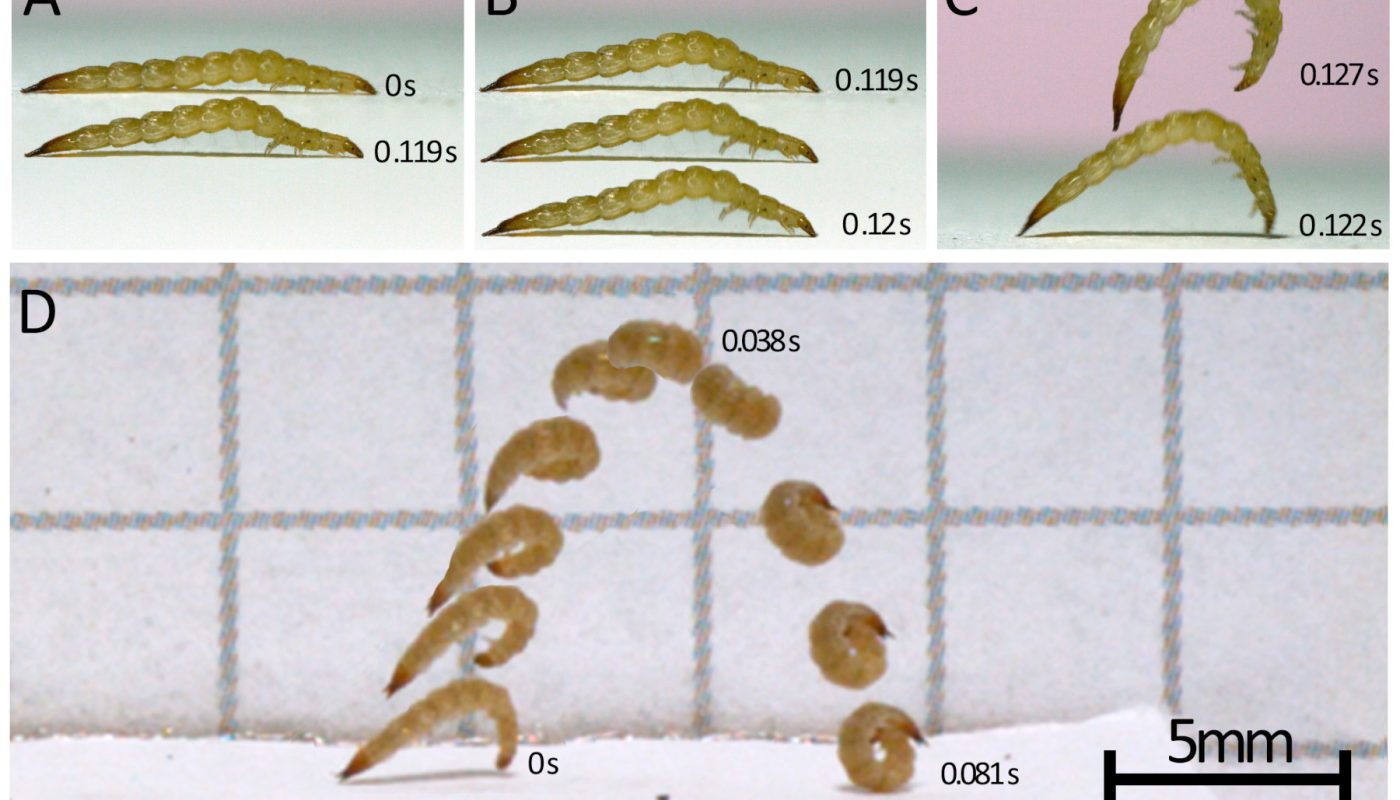

Insect larvae are typically thought of as worming their way around their environment, legless and slow-moving– or even stable. A paper released in PLOS ONE the other day (January 19) reports a strange behavior in the larvae of Laemophloeus biguttatus, typically known as the lined flat bark beetle: leaping. This fast locomotion was formerly unidentified in this insect types, according to the authors of the paper, and has actually only been frequently observed in fly maggots.matt bertoneThe research study team gathered and determined beetle larvae from the North Carolina State University school in 2019. They shot the jumping larvae with a high-speed electronic camera to catch their movements. They likewise evaluated the muscle mass of the developing beetles using microCT scans and SEM imaging to further examine the mechanism behind the tense bugs. The authors report that the Laemophloeus biguttatus beetle larvae can leap even more than their body length both horizontally and vertically.The larvae release themselves into the air by grasping soil with their legs while arching their bodies, then rapidly curling inward after releasing their grip on the soil. The researchers determine this method as “latch-mediated spring actuation,” a typical mechanism pests use to introduce themselves into the air. In these beetle larvae, the lock is not formed by one body part gripping another body part as in other invertebrates such as locusts and springtails, but rather by the legs holding the soil or substrate beneath the animal.In a discussion with The Scientist, North Carolina State University entomologist Matt Bertone discusses how he initially noticed these dives, the mechanism behind the behavior, and prospective reasons why larvae leap.The Scientist: How was this paper inspired [ or] started?Matt Bertone: This was truly serendipitous. Essentially, there was a standing dead pine tree outside of our lab on school that had some good fungus that was growing on it under the bark. Thats a terrific place to search for pests … Basically, I went to look at the tree and collected all different types of bugs from there, from beetles to bugs and termites, and things like that. I brought them back to the laboratory and as I was preparing and putting these larvae on pieces of bark to take pictures, I noticed they would walk a little bit and after that hop. I resembled, Thats actually unusual. Ive never ever become aware of that before and browsed a bit and couldnt discover anything about that.I was in a seminar with Dr. Adrian Smith, whos at the NC Museum of Natural Sciences, and he does a great deal of actually terrific high-speed recording and videography. Weve been discussing jobs to deal with, and I was like, Oh, hi, I simply found this little larva that looks like its leaping. Lets tape-record it. When we got the high-speed recordings … I sent it to a couple of colleagues who are experts on beetles, and none had ever become aware of that taking place or seen that happen.TS: What is special about this leaping habits in beetle larvae? MB: Jumping beetle larvae … [are] in fact fairly uncommon for such a large group of bugs. Theres over 350,000 species of described beetles in the world, and extremely few of them jump as larvae … When we saw the slow-motion video, we had the ability to see how it was really jumping which was even less typical– generally unique among pests. TS: Can you summarize steps in your research process?MB: We initially filmed [the larvae] at 3,000 frames per second or two … and we could see what was occurring and how they were jumping, however we didnt see some minute elements of it. [Smith] in fact recorded at 60,000 frames per 2nd and we had the ability to see a lot more unique steps in the process. As soon as we did that, we also took a look at the larvae under a scanning electron microscopic lense to see if there were any unique features or anatomy that might assist them leap … We likewise examined the literature … to put them in context of the other kinds of bugs that have leaping larvae. Because context, these [larvae] are really unique.TS: Can you explain how these larvae leap?MB: They were doing this latch-mediated spring actuation. Essentially, they lock on to something, develop energy in their body, and then launch the lock. That releases all the energy. What was special about this is that they were utilizing their claws to grip this substrate, the ground, and that was where they were latching. There are other bugs that have locking mechanisms and do this [where] they in fact have a body-part-to-body-part sort of lock, rather than a body part to the substrate. [ these larvae] dont need to establish 2 body parts to lock on to each other.We welcomed Joshua Gibson at University of Illinois, an expert in these locking systems and in energy … he did a CT scan of the larvae to look at the musculature inside. Basically, if we understand how much power a muscle puts out, and we understand just how much muscle [the larvae] have, we can see just how much power it would take to have them jump the way they did, and their strength and speed. Even though [the jump is] not incredibly effective or very record breaking, it was more than the muscles alone could power. That led us also to show that this is some kind of lock where theres the kept energy thats released.Representative launch series of leaping L. biguttatus larvaADRIAN SMITHTS: Do you have any speculations or concepts [regarding] why the beetle larvae do this? MB: First of all, we eliminated that they were doing this usually, since they typically live under bark. Theres really no area to leap around. Another idea was that it was some sort of artefact of what they do under the bark that might be equated to [a] jumping mechanism outside, however they did it so readily … When they felt the requirement, they would simply hop. They also really didnt respond specifically if you touch them with something. They will get a little irritated, and they d walk away, and they d hop. Our finest hypothesis based upon all this info is that due to the fact that they live on this decaying wood and under bark, these resources are … basically not around for a long period of time. They decay. They fall apart. We can picture a situation where the bark falls off a tree and exposes these larvae, and theyre light-colored versus a dark background. Theyre easy for predators to identify. This jumping in fact costs less energy than to crawl. It might be that they just utilize this to get out of a bad situation rapidly, and randomly discover a better scenario because they cant really direct their jumps. They type of go all over the place. Its not extremely advanced, however it is an energy reliable way to move around.TS: Were there any obstacles throughout the procedure? MB: Although this types is common throughout mostly [the] eastern US, and probably one of the most typical of the types of this group of beetles, they are relatively tiny. Theyre in these extremely ephemeral resources, these fungis that grow on dead trees and things like that for a little duration of time, and then get committed other fungi and other organisms. Finding enough larvae to be able to experiment on was one of the obstacles. We were truly fortunate to have found … a couple lots specimens. They dont live very long … If we had more specimens that were healthy and acting naturally, then we could kind of control [ experiments] in methods to see what triggered them to jump. However since we just had a limited number, we were just able to truly describe the jumping and present this as a brand-new finding.TS: Where do you see the future of this research study going? MB: It d be terrific if other scientists who find [the larvae] were to press the studies further and look at other reasons they might jump or if there are other species that may jump as well.TS: What do you want readers to eliminate from these observations? MB: Adrian published a video about jumping fly larvae maggots, and we in fact discovered a variety of them under the exact same bark that were leaping also … There are great deals of different flies that do this. They have a very widely known mechanism for doing it. At the end of this video that Adrian produced, he did a little teaser for this jumping beetle larvae … A researcher, a specialist in this group of beetles from Japan, saw the video and stated, Oh, Ive seen larvae do that, too. It was a different genus, in the same household … We do know [that] the dives in genuine time look almost identical, or really similar, although [these 2 beetle types] are not super closely associated. This all leads to us thinking that [larvae leaping might be] more widespread within either this group of beetles and even close relatives. I definitely encourage people to look under the bark– responsibly– on dead logs and dead trees and take a look at living things and see how they do what they do.Editors note: This interview has actually been modified for brevity.

A paper published in PLOS ONE the other day (January 19) reports a strange habits in the larvae of Laemophloeus biguttatus, frequently understood as the lined flat bark beetle: leaping. The authors report that the Laemophloeus biguttatus beetle larvae can jump further than their body length both horizontally and vertically.The larvae launch themselves into the air by grasping soil with their legs while arching their bodies, then rapidly curling inward after launching their grip on the soil. Weve been talking about jobs to work on, and I was like, Oh, hello, I just discovered this little larva that looks like its leaping. Once we did that, we likewise looked at the larvae under a scanning electron microscope to see if there were any unique functions or anatomy that may help them leap … We also evaluated the literature … to put them in context of the other types of pests that have jumping larvae. MB: Adrian published a video about leaping fly larvae maggots, and we really found a number of them under the very same bark that were jumping as well … There are lots of different flies that do this.