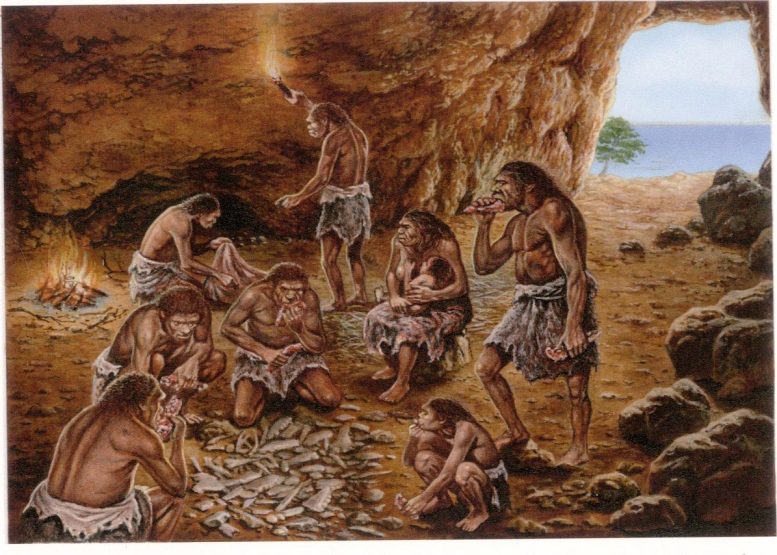

Restoration of meat roasting on campfire at the Lazaret Cave, France. Credit: De Lumley, M. A.

Yafit Kedar describes that the usage of fire by early human beings has been widely debated by scientists for numerous years, regarding concerns such as: At what point in their advancement did humans find out how to control fire and ignite it at will? Did they use the inner space of the cavern efficiently in relation to the fire?

Yafit Kedar: “One focal problem in the debate is the place of hearths in caves occupied by early human beings for extended periods of time. Multilayered hearths have actually been found in lots of caves, showing that fires had been lit at the exact same spot over many years. In previous studies, using a software-based design of air circulation in caves, together with a simulator of smoke dispersal in a closed space, we found that the optimal area for minimal smoke exposure in the winter season was at the back of the cave. The least beneficial location was the caves entrance.”

Excavations at the Lazaret Cave, France. Credit: De Lumley, M. A.

In the existing study the researchers applied their smoke dispersal design to a thoroughly studied ancient website– the Lazaret Cave in southeastern France, populated by early human beings around 170-150 thousand years ago. Yafit Kedar: “According to our model, based on previous studies, putting the hearth at the back of the cavern would have decreased smoke density to a minimum, enabling the smoke to flow out of the cave right beside the ceiling. In the archaeological layers we took a look at, the hearth was situated at the center of the cave. We attempted to comprehend why the occupants had chosen this area, and whether smoke dispersal had been a significant consideration in the caverns spatial division into activity areas.”

To address these concerns, the scientists performed a variety of smoke dispersal simulations for 16 theoretical hearth areas inside the 290sqm cavern. For each hypothetical hearth they evaluated smoke density throughout the cavern utilizing thousands of simulated sensing units placed 50cm apart from the floor to the height of 1.5 m.

To understand the health ramifications of smoke direct exposure, measurements were compared to the typical smoke exposure recommendations of the World Health Organization. In this way four activity zones were mapped in the cave for each hearth: a red zone which is basically out of bounds due to high smoke density; a yellow area ideal for short-term profession of a number of minutes; a green location ideal for long-lasting profession of numerous hours or days; and a blue location which is basically smoke-free.

Yafit and Gil Kedar: “We found that the average smoke density, based upon determining the number of particles per spatial system, remains in truth very little when the hearth lies at the back of the cave– just as our design had actually anticipated. We likewise discovered that in this circumstance, the area with low smoke density, most suitable for extended activity, is fairly far-off from the hearth itself.

Early humans required a balance– a hearth near to which they could work, cook, consume, sleep, get together, warm themselves, and so on while exposed to a minimum amount of smoke. Ultimately, when all needs are taken into account– daily activities vs. the damages of smoke exposure– the residents placed their hearth at the ideal spot in the cave.”

The study identified a 25sqm area in the cavern which would be optimal for locating the hearth in order to enjoy its advantages while preventing excessive direct exposure to smoke. Remarkably, in the numerous layers examined by in this research study, the early human beings in fact did place their hearth within this area.

Prof. Barkai concludes: “Our study shows that early humans were able, without any sensors or simulators, to pick the ideal location for their hearth and handle the caves area as early as 170,000 years earlier– long before the arrival of contemporary humans in Europe. This capability reflects ingenuity, experience, and prepared action, along with awareness of the health damage brought on by smoke exposure. In addition, the simulation design we developed can assist archaeologists excavating new sites, enabling them to search for hearths and activity areas at their ideal locations.”

In more research studies the researchers intend to utilize their design to examine the impact of various fuels on smoke dispersal, usage of the cavern with an active hearth at various seasons, use of a number of hearths concurrently, and other relevant concerns.

Reference: “The influence of smoke density on hearth area and activity locations at Lower Paleolithic Lazaret Cave, France” by Yafit Kedar, Gil Kedar and Ran Barkai, 27 January 2022, Scientific Reports.DOI: 10.1038/ s41598-022-05517-z.

Restoration of ancient human in the Lazaret Cave, France (Pay attention to the area of the hearth). Credit: De Lumley, M. A. néandertalisation (pp. 664-p). CNRS éditions.

Spatial preparation in caves 170,000 years earlier.

Findings suggest that early people understood a good deal about spatial preparation: they managed fire and utilized it for various requirements and placed their hearth at the optimum area in the cavern– to acquire optimal advantage while exposed to a minimum quantity of unhealthy smoke.

A cutting-edge research study in ancient archaeology at Tel Aviv University provides proof for high cognitive abilities in early humans who lived 170,000 years ago. In a first-of-its kind study, the scientists established a software-based smoke dispersal simulation design and applied it to a recognized ancient website. They discovered that the early people who occupied the cave had placed their hearth at the optimum place– allowing maximum utilization of the fire for their activities and needs while exposing them to a minimal amount of smoke.

The study was led by PhD trainee Yafit Kedar, and Prof. Ran Barkai from the Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures at TAU, together with Dr. Gil Kedar. The paper was published in Scientific Reports.

They found that the early people who inhabited the cave had put their hearth at the ideal location– making it possible for optimum utilization of the fire for their activities and needs while exposing them to a minimal quantity of smoke.

In previous studies, using a software-based design of air blood circulation in caverns, along with a simulator of smoke dispersal in a closed space, we discovered that the ideal area for minimal smoke exposure in the winter was at the back of the cave. Yafit Kedar: “According to our design, based on previous research studies, positioning the hearth at the back of the cave would have reduced smoke density to a minimum, allowing the smoke to circulate out of the cave right next to the ceiling. To respond to these concerns, the researchers performed a range of smoke dispersal simulations for 16 hypothetical hearth places inside the 290sqm cavern. For each theoretical hearth they evaluated smoke density throughout the cave utilizing thousands of simulated sensors put 50cm apart from the flooring to the height of 1.5 m.

To understand the health implications ramifications smoke exposureDirect exposure measurements were compared with the average typical exposure recommendations of the World Health OrganizationCompany