This post was very first published in The Conversation.

Jonti Horner– Professor (Astrophysics), University of Southern Queensland.

Tanya Hill– Honorary Fellow of the University of Melbourne and Senior Curator (Astronomy), Museums Victoria.

In 1995, comet SW3 unexpectedly and suddenly lightened up. The comet had catastrophically fragmented, releasing substantial quantities of dust, debris, and gas.

Has the particles spread far enough to experience Earth? It depends on how much particles was ejected in 1995 and how rapidly that particles was flung outwards as the comet fell apart. The pieces of dust and particles are so small we cant see them till we run into them.

Artists impression of the 1833 Leonid meteor storm. Credit: Adolf Vollmy (April 1888).

A minor shower called the Tau Herculids could produce a meteor storm for observers in the Americas this week. While some websites promise “the most powerful meteor storm in generations,” astronomers are a little bit more careful.

Introducing comet SW3.

The story begins with a comet called 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 3 (comet SW3 for short). First spotted in 1930, it is responsible for a weak meteor shower called the Tau Herculids, which nowadays appears to radiate from a point about 10 degrees from the intense star Arcturus.

In 1995, comet SW3 suddenly and suddenly lightened up. A number of outbursts were observed over a couple of months. The comet had catastrophically fragmented, launching substantial amounts of debris, dust, and gas.

By 2006 (2 orbits later on), comet SW3 had disintegrated even more, into several bright pieces accompanied by numerous smaller chunks.

Pieces of comet 73P seen by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2006. Credit: NASA, ESA, H. Weaver (APL/JHU), M. Mutchler and Z. Levay (STScI).

Is Earth on a clash?

This year, Earth will cross comet SW3s orbit at the end of May.

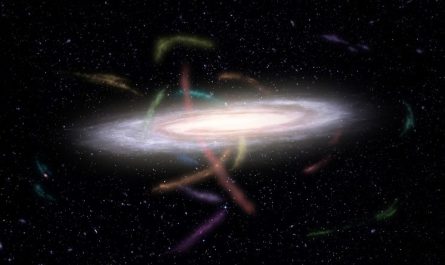

In-depth computer modeling recommends particles has actually been spreading out along the comets orbit like huge thin arms in space.

Has the debris spread far enough to encounter Earth? It depends on how much particles was ejected in 1995 and how rapidly that particles was flung outwards as the comet fell apart.

Could history repeat itself?

Our existing understanding of meteor showers began 150 years ago with an event quite comparable to SW3s story.

A comet called comet 3D/Biela was discovered in 1772. It was a short-period comet, like SW3, returning every 6.6 years.

In 1846, the comet started to act strangely. Observers saw its head had actually split in 2, and some described an “archway of cometary matter” in between the pieces.

Sketch of comet 3D/Biela in February 1846, after it split into (at least) two pieces. Credit: Edmund Weiß.

At the comets next return, in 1852, the two pieces had actually plainly separated and both were changing unpredictably in brightness.

The comet was never seen again.

In late November of 1872, an unforeseen meteor storm graced northern skies, stunning observers with rates of more than 3,000 meteors per hour.

The meteor storm of 1872. Credit: Amedee Guillemin.

The meteor storm took place when the Earth crossed 3D/Bielas orbit: it was where the comet itself ought to have been two months earlier. A second storm, weaker than the very first, took place in 1885, when the Earth once again encountered the comets remains.

3D/Biela had actually broken down into debris, but the two great meteor storms it produced served as a fitting wake.

A passing away comet, falling apart before our eyes, and an associated meteor shower, normally barely invisible versus the background noise. Are we ready to see history repeat itself with comet SW3?

What does this suggest for the Tau Herculids?

The primary difference between the events of 1872 and this years Tau Herculids boils down to the timing of Earths crossing of the cometary orbits. In 1872, Earth crossed Bielas orbit several months after the comet was due, going through product dragging where the comet would have been.

By contrast, the encounter in between Earth and SW3s debris stream next week happens numerous months before the comet is due to reach the crossing point. The debris requires to have spread ahead of the comet for a meteor storm to take place.

Could the particles have spread far enough to experience Earth? Some designs recommend well see a strong display from the shower, others recommend the particles will fall just short.

Do not count your meteors before theyve flashed!

Whatever takes place, observations of next weeks shower will considerably improve our understanding of how comet fragmentation events occur.

Computations reveal Earth will cross SW3s orbit at about 3 pm, May 31 (AEST). If the particles reaches far enough forward for Earth to experience it, then an outburst from the Tau Herculids is likely, but it will just last an hour or two.

From Australia, the show (if there is one) will be over prior to its dark enough to see whats occurring.

For observers throughout Australia, the Tau Herculids radiant is low in the northern sky around 7 pm regional time. Credit: Museums Victoria/Stellarium.

Observers in North America and South America will, nevertheless, have a ringside seat.

They are more most likely to see a moderate display of slow-moving meteors than a big storm. This would be an excellent outcome, but might be a little frustrating.

There is a chance the shower could put on a genuinely spectacular screen. Astronomers are traveling throughout the world, simply in case.

What about Australian observers?

Theres also a little opportunity any activity will last longer than anticipated, or even show up a bit late. Even if youre in Australia, its worth looking up on the evening of May 31, just in case you can get a peek of a piece from a passing away comet!

The 1995 particles stream is simply one of lots of laid down by the comet in past decades.

By midnight (local time), the Tau Herculids glowing will have relocated to the north-western sky, seen from throughout Australia. Credit: Museums Victoria/Stellarium.

During the morning of May 31, around 4 am (AEST), Earth will cross debris from the comets 1892 passage around the Sun. Later that evening, around 8 pm, May 31 (AEST), Earth will cross particles set by the comet in 1897.

Particles from those sees will have spread out over time, and for that reason we anticipate only a couple of meteors to grace our skies from those streams. As always, we might be wrong– the only method to understand is to go out and see!

Written by:.

The 1833 Leonid Meteor storm, as seen over Niagara Falls. Credit: Edmund Weiß (1888 )

As Earth orbits the Sun, it plows through dust and particles left behind by comets and asteroids. That particles brings to life meteor showers– which can be one of natures most amazing displays.

Many meteor showers are foreseeable, recurring each year when the Earth passes through a particular trail of debris.

On celebration, however, Earth goes through a particularly narrow, dense clump of debris. This results in a meteor storm, sending thousands of shooting stars spotting throughout the sky each hour.