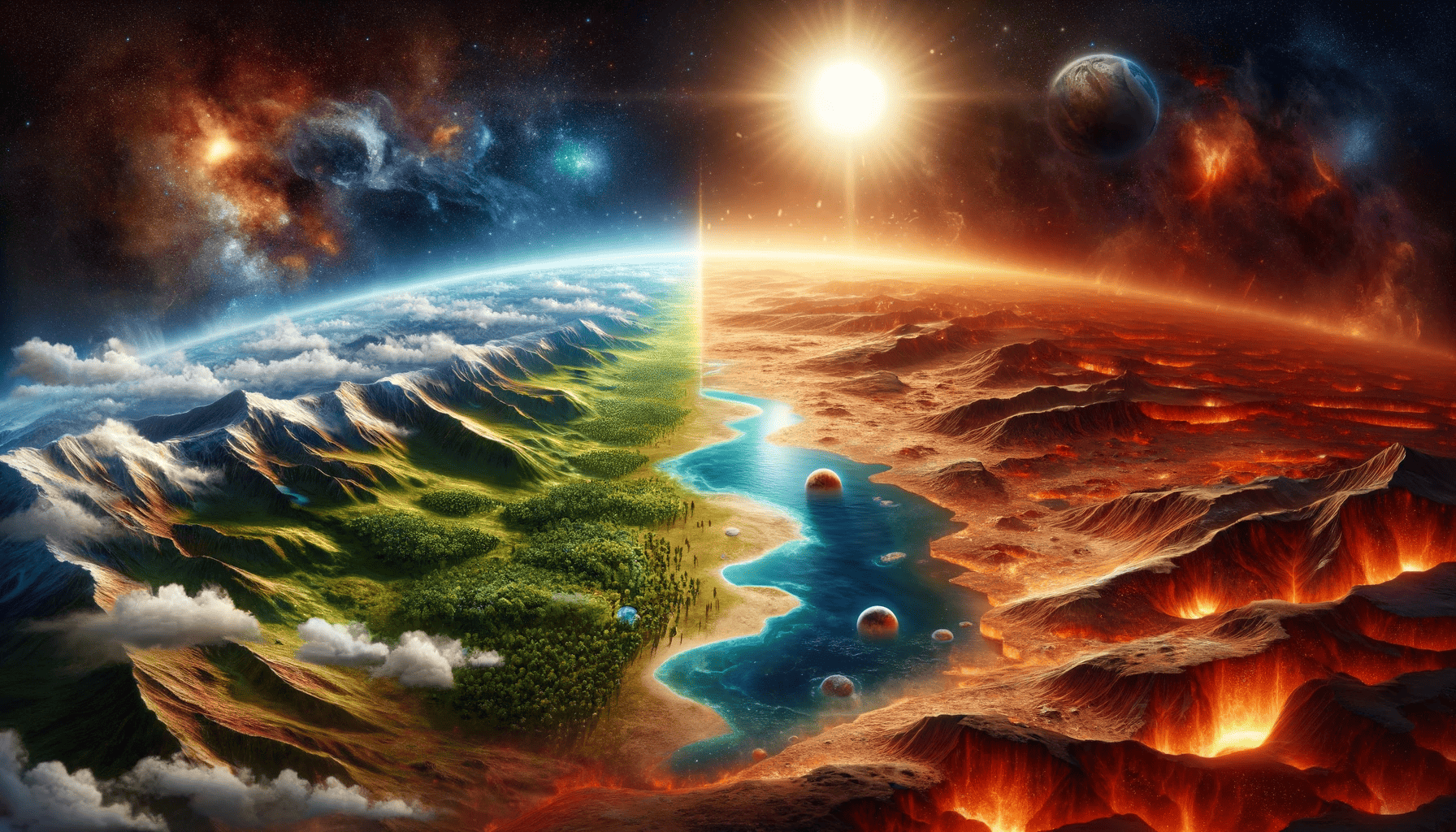

For the first time, scientists have managed to simulate the entirety of the runaway greenhouse gas process which can transform the climate of a planet from perfect for life to a place more than harsh. This holds significance for our understanding of extrasolar planets, also called exoplanets, and also provides valuable insights into the climate crisis affecting Earth.

The researchers showed that from the initial stages of the process, the atmospheric structure and cloud coverage go through big changes – leading to a difficult-to-reverse runaway effect. On Earth, a rise of just a few tens of degrees of the global average temperature followed by a rise in the Sun’s luminosity would be enough to start this process and make it inhabitable.

“Until now, other key studies in climatology have focused solely on either the temperate state before the runaway, or either the inhabitable state post-runaway,” Martin Turbet, study author, said in a news release. “It is the first time a team has studied the transition itself with a 3D global climate model, and has checked how the climate and the atmosphere evolve during that process.”

The concept of a runaway greenhouse effect is not a novel one. In this situation, a planet has the potential to transition from a temperate state, resembling Earth, to a nightmarish environment with surface temperatures surpassing 1000°C. The culprit? Water vapor, a natural greenhouse gas.

Water vapor prevents the solar radiation absorbed by Earth from being reemitted into the void of space as thermal radiation. It acts as a thermal blanket, trapping heat like a rescue blanket. A moderate greenhouse effect is beneficial – without it, Earth would exhibit an average temperature below the freezing point of water, resembling a frigid, ice-covered sphere inhospitable to life.

Conversely, an excessive greenhouse effect intensifies ocean evaporation, leading to a higher concentration of water vapor in the atmosphere. “There exists a critical threshold for this level of water vapor, beyond which the planet loses its ability to cool down. Beyond this point, conditions spiral out of control,” Guillaume Chaverot, study author, said in a news release.

Unique clouds

A crucial aspect of the study highlights the emergence of an exceptionally unique cloud pattern that amplifies the runaway effect, rendering the process irreversible. “At the onset of the transition, we witness the formation of highly dense clouds in the upper atmosphere. In fact, the atmosphere no longer exhibits the temperature inversion typically found in the Earth’s atmosphere,” Chaverot said.

Utilizing their climate models, the scientists determined that even a marginal increase in solar irradiation, resulting in a global temperature rise of just a few tens of degrees, could instigate an irreversible runaway process on Earth, transforming our planet into an inhospitable environment akin to Venus – it’s 100 times hotter than Earth and has a thick atmosphere.

A current objective in climate action is to restrict global warming caused by greenhouse gases to 1.5 degrees by 2050. The researchers aren’t yet sure whether greenhouse gases could induce the runaway process in a manner similar to a slight elevation in solar luminosity. If so, the next question would be to establish whether the threshold temperatures are consistent for both processes.

“Assuming this runaway process would be started on Earth, an evaporation of only 10 meters of the oceans’ surface would lead to a 1 bar increase of the atmospheric pressure at ground level. In just a few hundred years, we would reach a ground temperature of over 500°C. Later, we would even reach 273 bars of surface pressure and over 1 500°C,” Chaverot said.

The study is also a key feature in the examination of climates on other planets, especially exoplanets—those orbiting stars other than the Sun. “When delving into the study of planetary climates, one of our primary objectives is to assess their potential to sustain life,” Émeline Bolmont, co-author of the study, said in a news release.

The study was published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.