Every piece consists of billions of microorganisms– and they are what makes cheeses tasty and distinctive.

When Wolfes group and others examined mature cheeses, they discovered that the microbial blends– microbiomes– of the cheeses revealed only a passing similarity to those cultures. In some cheeses, more than 400 different kinds have been discovered, says Mayo, who has actually examined microbial interactions in the cheese ecosystem. A study in 2020 that looked at 55 artisanal Irish cheeses discovered that practically one in three cheese microorganisms possessed genes required to produce “weapons”– chemical substances that eliminate off rivals. Like microbes on a rotten log in the woods, the germs and fungi in cheese break down their environment– in this case, the milk fats and proteins.

Some cheeses are moderate and soft like mozzarella, others are salty-hard like Parmesan. And some odor pungent like Époisses, a funky orange cheese from the Burgundy region in France.

There are cheeses with fuzzy skins such as Camembert, and ones marbled with blue veins such as Cabrales, which ripens for months in mountain caverns in northern Spain.

Yet almost all of the worlds thousand-odd type of cheese begin the exact same, as a white, rubbery swelling of curd.

How do we receive from that uniform blandness to this cornucopia? The answer focuses on microbes. Cheese bursts with yeasts, germs and molds. “More than 100 various microbial species can easily be found in a single cheese type,” says Baltasar Mayo, a senior scientist at the Dairy Research Institute of Asturias in Spain. Simply put: Cheese isnt just a treat, its an ecosystem. Every slice consists of billions of microorganisms– and they are what makes cheeses unique and scrumptious.

People have made cheese because the late Stone Age, however only just recently have scientists begun to study its microbial nature and discover the fatal skirmishes, serene alliances and beneficial collaborations that happen in between the organisms that call cheese house.

To discover out what germs and fungis exist in cheese and where they come from, researchers sample cheeses from all over the world and extract the DNA they consist of. By matching the DNA to genes in existing databases, they can identify which organisms are present in the cheese. “The method we do that is sort of like microbial CSI, you understand, when they go out to a criminal activity scene investigation, however in this case we are looking at what microorganisms are there,” Ben Wolfe, a microbial ecologist at Tufts University, likes to state.

Cheesemakers frequently add starter cultures of helpful bacteria to freshly formed curds to assist a cheese on its method. When Wolfes group and others took a look at ripened cheeses, they found that the microbial mixes– microbiomes– of the cheeses showed just a passing resemblance to those cultures.

People have been making cheese for thousands of years. This illustration from a 14th century manuscript reveals medieval Europeans making cheese– and eating it.CREDIT: TACUINUM SANITATIS/ WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

A lot of these microorganisms ended up being old acquaintances, however ones we usually understand from locations besides cheese. Take Brachybacterium, a microorganism present in Gruyère, which is more frequently found in soil, seawater and chicken litter (and possibly even an Etruscan tomb). Or germs of the genus Halomonas, which are typically connected with salt ponds and marine environments.

Theres Brevibacterium linens, a bacterium that has actually been recognized as a main factor to the stinkiness of Limburger. When we state that filthy feet smell “tacky,” theres reality to it: The exact same organisms are involved. (An artist in Ireland showed this some years earlier by culturing cheeses with organisms plucked from individualss bodies.).

Initially, scientists were surprised by how some of these microorganisms wound up on and in cheese. As they sampled the environment of cheesemaking centers, a photo began to emerge. The milk of cows (or goats or sheep) includes some microorganisms from the get-go. However a lot more are gotten during the milking and cheesemaking process. Soil germs hiding in a stables straw bed linen may connect themselves to the teats of a cow and wind up in the milking pail, for instance. Skin germs fall under the milk from the hand of the milker or get transferred by the knife that cuts the curd. Other microorganisms go into the milk from the tank or merely wander down off the walls of the dairy facility.

Some microbes are probably brought in from surprisingly far. Wolfe and other scientists now suspect that marine microbes such as Halomonas get to the cheese via the sea salt in the brine that cheesemakers use to wash down their cheeses.

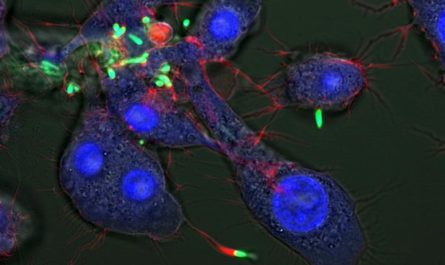

Every cheese is an environment of fungi and germs. These microorganisms were separated from the skin of a Vermont blue cheese. The orange colonies with ruffled edges are the bacterium Staphylococcus xylosus and the white ones are S. succinus. The small round nests are a number of species of Brevibacterium, and the fuzzy white colony is a Penicillium mold.CREDIT: COURTESY OF THE WOLFE LAB, TUFTS UNIVERSITY.

A basic, fresh white cheese like petit-suisse from Normandy might mostly include microorganisms of a single types or two. In some cheeses, more than 400 various kinds have actually been discovered, states Mayo, who has examined microbial interactions in the cheese ecosystem.

Consider Bethlehem, a raw milk cheese made by Benedictine nuns in the Abbey of Regina Laudis in Connecticut. A single gram of skin from a completely mature cheese might contain an excellent 10 billion germs, yeasts and other fungis.

Typically, the first microbial settlers in milk are lactic acid bacteria (LABs). The increasing acidity triggers the milk to sour, making it inhospitable for lots of other microbes.

A choose few microorganisms can abide this acid environment, among them certain yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (bakers yeast). These microorganisms move into the souring milk and eat the lactic acid that LABs produce. In doing so, they reduce the effects of the acidity, ultimately enabling other bacteria such as B. linens to sign up with the cheesemaking party.

A study in 2020 that looked at 55 artisanal Irish cheeses discovered that nearly one in 3 cheese microorganisms possessed genes required to produce “weapons”– chemical compounds that kill off rivals. At this point it isnt clear if and how numerous of these genes are switched on, states Cotter, who was included in the job.

Cheese microorganisms also cooperate. For instance, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts that eat the lactic acid produced by the LABs return the favor by making vitamins and other substances that the LABs require. In a various sort of cooperation, threadlike fungal filaments can act as “roadways” for surface germs to travel deep into the interior of a cheese, Wolfes team has actually discovered.

By now you might have started to suspect: Cheese is basically about decomposition. Like microbes on a rotten log in the woods, the bacteria and fungi in cheese break down their environment– in this case, the milk fats and proteins. This makes cheeses creamy and provides them taste.

Mom Noella Marcellino, a long time Benedictine cheesemaker at the Abbey of Regina Laudis, put it this way in a 2021 interview with Slow Food: “Cheese reveals us what goodness can come from decay. Decay produces this wonderful fragrance and taste of cheese while evoking a pledge of life beyond death.”.

Exactly how the microorganisms develop taste is still being examined. “Its much less comprehended,” states Mayo. But a couple of things currently stick out. Lactic acid germs, for example, produce unstable compounds called acetoin and diacetyl that can likewise be found in butter and appropriately give cheeses a rich, buttery taste. A yeast called Geotrichum candidum produces a mix of alcohols, fats and other substances that impart the musty yet fruity fragrance quality of cheeses such as Brie or Camembert. Theres butyric acid, which smells rancid on its own however enhances the scent of Parmesan, and unpredictable sulfur substances whose cooked-cabbage smell blends into the flavor profile of many mold-ripened cheeses like Camembert. “Different strains of microorganism can produce different taste parts,” says Cotter.

All a cheesemaker does is set the right conditions for the “rot” of the milk. “Different germs and fungi grow at various temperatures and various humidity levels, so every step along the way introduces range and nuance,” says Julia Pringle, a microbiologist at the artisan Vermont cheesemaker Jasper Hill Farm. If a cheesemaker warms the milk to over 120 degrees Fahrenheit, for instance, only heat-loving bacteria like Streptococcus thermophilus will make it through– ideal for making cheeses like mozzarella.

Cutting the curd into large pieces implies that it will retain a reasonable quantity of wetness, which will cause a softer cheese like Camembert. On the other hand, small cubes of curd drain much better, resulting in a drier curd– something you want for, state, a cheddar.

Saving the young cheese at warmer or cooler temperature levels will once again motivate some microbes and inhibit others, as does the quantity of salt that is added. When cheesemakers clean their ripening rounds with brine, it not only imparts seasoning but likewise promotes nests of salt-loving bacteria like B. linens that quickly create a specific kind of rind: “orangey, a bit sticky, and kind of funky,” states Pringle.

Vermont cheesemaker John Putnam (a former attorney) is “dipping the curd”– that is, collecting the curdled milk into a square of cheesecloth so that the liquid whey can drain off the newborn cheese. Microbes from the walls, the cheesecloth and Putnam himself will all settle into the milk, assisting to determine the flavor of the final cheese.CREDIT: H. PAXSON/ GASTRONOMICA 2010.

Even the smallest modifications in how a cheese is managed can alter its microbiome, and thus the cheese itself, cheesemakers say. Turn on the air exchanger in the ripening space by mistake so that more oxygen streams around the cheese and suddenly molds will grow that have not been there in the past.

But surprisingly, as long as the conditions stay the exact same, the very same neighborhoods of microbes will reveal up once again and again, scientists have found. Put in a different way: The same microbes can be found practically all over. If a cheesemaker sticks to the recipe for a Camembert– constantly warms the milk to the appropriate temperature level, cuts the curd to the best size, ripens the cheese at the appropriate temperature and moisture level– the same species will thrive and a nearly similar kind of Camembert will develop, whether its on a farm in Normandy, in a cheesemakers collapse Vermont or in a steel-clad dairy factory in Wisconsin.

Some cheesemakers had actually speculated that cheese was like white wine, which famously has a terroir– that is, a specific taste that is connected to its geography and is rooted in the vineyards microclimate and soil. Apart from subtle nuances, if everything goes well in production, the exact same cheese type constantly tastes the same no matter where or when its made, says Mayo.

Somerville research studies genomic changes in cheese starter cultures utilized in his nation. In Switzerland, cheesemakers traditionally hold back part of the whey from a batch of cheese to utilize once again when making the next one.

Not just has cheesemaking become tamer over time, it is also cleaner than it utilized to be– and this has actually had consequences for its ecosystem. These days, numerous cows are milked by devices and the milk is siphoned directly into the closed systems of hermetically sealed, ultra-filtered storage tanks, safeguarded from the consistent rain of microorganisms from hay, human beings and walls that picked the milk in more traditional times.

Typically the milk is pasteurized, too– that is, briefly warmed to high temperatures to kill the bacteria that come naturally with it. Theyre replaced with standardized starter cultures.

All of this has actually made cheesemaking more controlled. However alas, it also suggests that theres less variety of microbes in our cheeses. Much of our provolones, camemberts and cheddars, as soon as extremely proliferating microbial meadows, have actually become more like manicured lawns. And because every microbe contributes its own signature mix of chemical substances to a cheese, less variety likewise means less flavor– a big loss.

This article initially appeared in Knowable Magazine, an independent journalistic undertaking from Annual Reviews. Register for the newsletter.